By Jorge Rolón Luna**

Contract killings are nothing new in Paraguay. Common sense tends to restrict and limit them to certain places on the border — especially but not exclusively to the department of Amambay — so it is common to observe that when they occur in the country’s capital they generate reactions of unusual fear, repulsion, and sometimes even astonishment. These reactions are usually followed by comments such as: “it doesn’t just happen on the border anymore”. Now, to what extent are the sicarios -no case of “sicarias” has been reported yet- shedding the blood of victims in more and more places in the country?

To answer the question, I will use an analogy with the concept of “oil slick”. To understand this, it is necessary to consider how oil spills behave in the sea. In these cases, the oil inexorably spreads, covers extensive surfaces and in the process produces terrible effects on the fauna, flora and other forms of marine life, compromising all the impacted ecosystems. Something similar happens with the sicariato. The phenomenon is growing not only quantitatively but also geographically, extending to different ends of the country, ending human lives and, at the same time, imposing its logic of terror, blackmail, corruption and undermining civil and political life.

The sicariato is a byproduct of high-level criminal networks in which the state, politics, and the mafia are associated. In Paraguay, its advance has oscillated between denial and indifference. This has been possible because assassination was considered a “narco thing”, without taking into account the lives that were lost, since they were “nothing more” than “frontiersmen”, “mafiosi”, in other words, people who did not deserve to be mourned. In the face of its expansion, today it seems too late to try to find quick and easy solutions to this phenomenon.

Something similar happened with the phenomenon of the maras (gangs) in El Salvador, says one of the most authoritative voices on the subject, Salvadoran anthropologist Juan Martinez d’Aubuisson: “the Salvadoran state only paid attention to the phenomenon when it began to expand beyond the poor neighborhoods, until the situation finally escaped its control.”

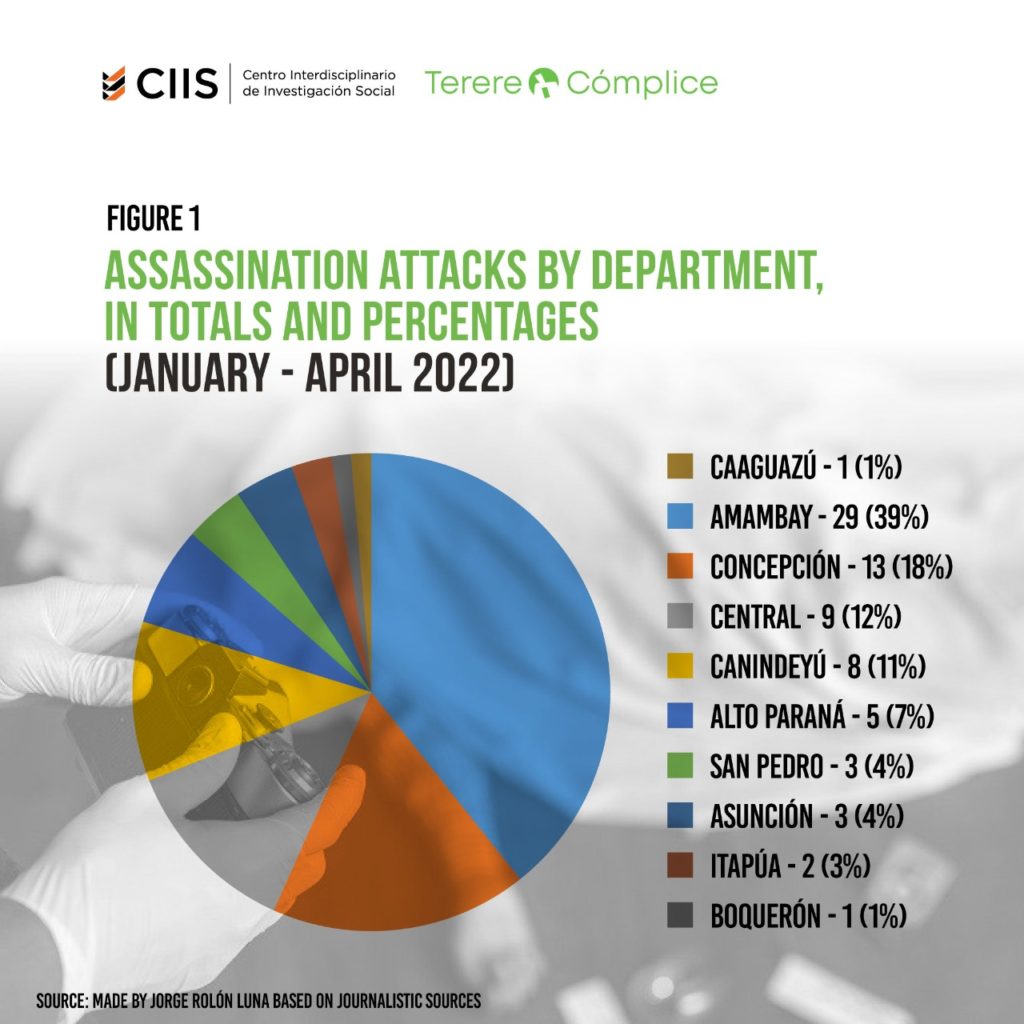

In Paraguay, the fear of hired assassination cases has increased with the repetition of this phenomenon. Today it happens almost daily, with alarming frequency, and spills out of the traditional territories. The geolocation of the hitmen attacks in the first 4 months of the year 2022, shows the following distribution.

Figure 1: Assassination attacks by department, in totals and percentages (January-April 2022)

Source: Author’s own figures based on journalistic sources.

Here something predictable stands out: Amambay tops the list. The most violent department in the country has 29 attacks in the first four months of the year, almost one attack every four days, amassing 39% of the total for the period. It is followed by a department that has been showing high and stable numbers for a long time, Concepción, with 13 cases, equivalent to 18% of the total, and in third place is Central, with 9 cases. The capital, Asunción, had 3 cases, 4% of the total. Next, we will see the data for the same period in the year 2021.

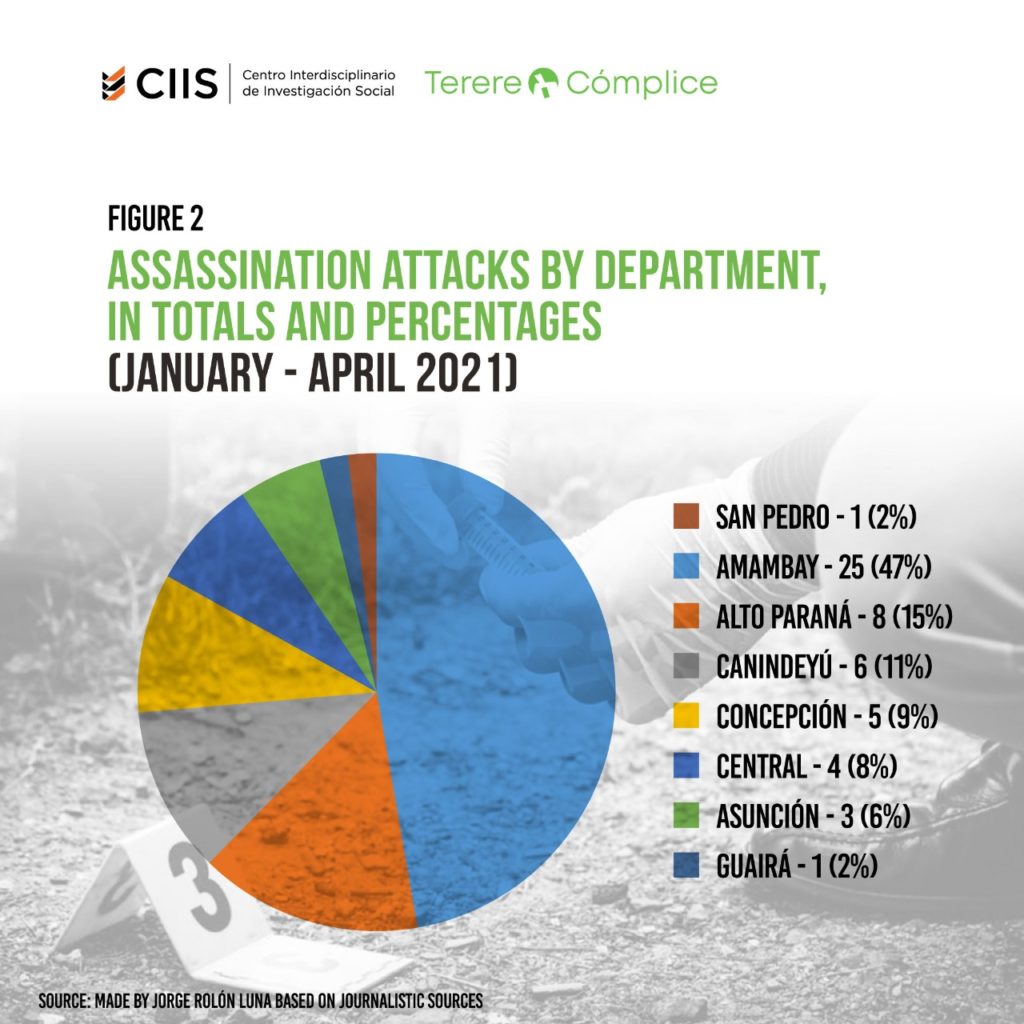

Figure 2: Assassination attacks by department, in totals and percentages (January-April 2021)

Source: Author’s own figures based on journalistic sources.

In the 2021 period, Amambay accounted for almost half of the cases, while the rest were distributed among 7 departments. The Department of Alto Paraná was in second place with 8 cases (15%), followed by Canindeyú with 6 cases (11%). Interestingly violence has already his Asuncion, with 3 cases. (6%).

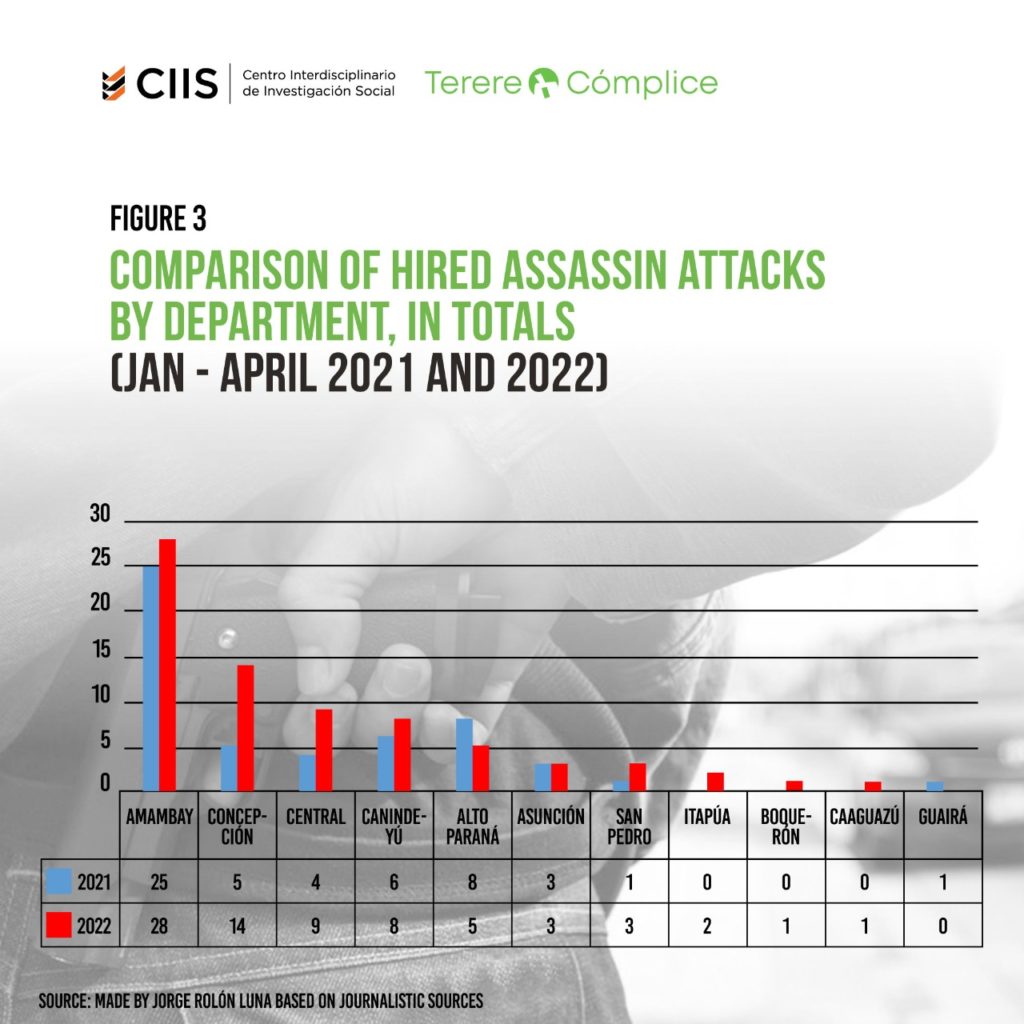

The comparison of these two periods by locality shows the predominance of Amambay, which, curiously, although it recorded more events in 2022 than in 2021 (29/25), its share of the total dropped from 47% to 39%. Between one year and the next, there was also significant growth in Concepción (9% to 18%) and Central (8% to 12%), while Asunción, although it had the same number of attacks, decreased its percentage share (6% to 4%).

Figure 3: Comparison of hired assassin attacks by department, in totals (Jan-April 2021 and 2022)

Source: Author’s own based on journalistic sources.

Source: Author’s own based on journalistic sources.

The data allow us to draw some conclusions. The “traditional” sicariato sphere is expanding, with Amambay, Concepción and Canindeyú firmly established as “narco-zones”. However, this expansion now extends to areas such as Asunción, Central and Alto Paraná. If one considers sicariato as a phenomenon fundamentally associated with the activity of criminal groups trafficking drugs, it has undoubtedly moved beyond the traditional “hot” border zone such as Amambay and is extending into Concepción, Canindeyú and, surprisingly, Central.

The sicariato is a byproduct of high-level criminal networks in which the state, politics, and the mafia are associated. In Paraguay, its advance has oscillated between denial and indifference. This has been possible because assassination was considered a “narco thing”, without taking into account the lives that were lost, since they were “nothing more” than “frontiersmen”, “mafiosi”, in other words, people who did not deserve to be mourned.

The causes are diverse, and although it is not the subject of this article, some hypotheses can be proposed: Concepción is too close to Brazil and the Paraguayan Chaco (with its airstrips that bring merchandise from Peru, Bolivia, and Colombia), Central plays a preponderant role in the river route along which cocaine travels to Europe and West Africa, in addition to the growing micro-trafficking business, all of which also involves Asunción.

The dispersion of the sicariato oil slick is giving us undeniable clues about the expansion of a globalized business such as cocaine, with all the death it brings with it.

*This article was written before the assassination of anti-drug prosecutor Marcelo Pecci in Colombia.

** Lawyer, teacher and independent researcher. Former director of the Observatory of Security and Citizen Coexistence of the Ministry of the Interior.

Cover image: Crónica Newspaper