The need for practicality in the opposition (II): lists of senators, representatives and councilors

By Javier Lassalle

In the previous post I expressed the need for practicality in the agreement for the presidential and gubernatorial positions, justified by the fact that the NRA remains at levels close to 50% for those positions.

The elections for senators, representatives and departmental councilors also require some concrete practicality by the opposition coalition. Here the reasons are twofold: 1) the D’hondt system (used to allocate seats) punishes division, or seen in another way, rewards the most voted lists and; 2) the unblocking will make the ANR increase its voters to these lists.

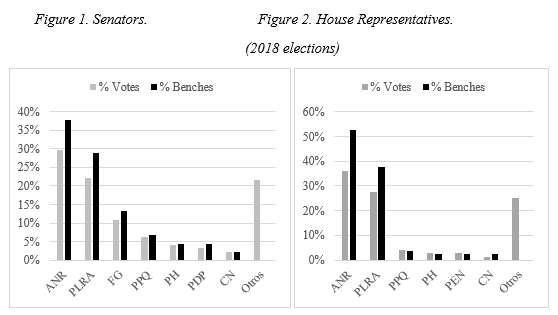

The D’hondt system punishes the small and benefits the big. Let’s see how the D’hondt system punishes division. The graphs show the percentage of votes for each list and the percentage of seats that each list obtained in the 2018 elections, for senators and deputies.

Source: TSJE.

Note how the large parties end up over-represented in the chambers and how the small parties lose representation. In the Senate election more than 20% of the votes ended up without representation and in the House of Representatives, over 25%. The D’hondt system punishes more the division when there are fewer seats at stake in the list, that is why this is greater in the house than in senators. Let us remember that the senate has a national list of 45 seats, while the lists of representatives is departmental and ranges from 1 to 20 seats, depending on the population of the department.

If the Concertation has only three or four lists (but the fewer the better), it will be a big step. The example of the municipal elections of 2021 should serve as a lesson, if not, let us see what happened to the progressive sector that made a process of “de-concertation” (the parties of the Frente Guasú presented two lists, and other progressives went to other lists) in Asunción. It went from four councilors to none.

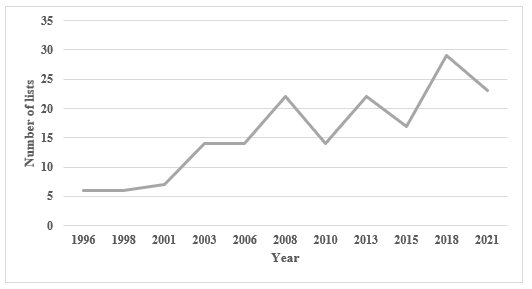

The D’Hondt system should always have been an incentive to more unity. However, if we analyze the data over time, we see in each election less unity. The opposition has not understood this for a generation. To see graphically how the opposition has not understood the D’Hondt system, Figure 3 plots the number of lists over time. The graph includes the number of lists for the senate and the Asuncion city council for the general and municipal elections, respectively. To maintain continuity, I mix lists for general and municipal elections. We see a constant increase of lists, which is detrimental to them.

Number of lists for councilors (in Asunción) in municipal elections (1996, 2001, 2006, 2006, 2010, 2015, 2011) and for the Senate in general elections (1998, 2003, 2008, 2013, 2018).

Source: TSJE.

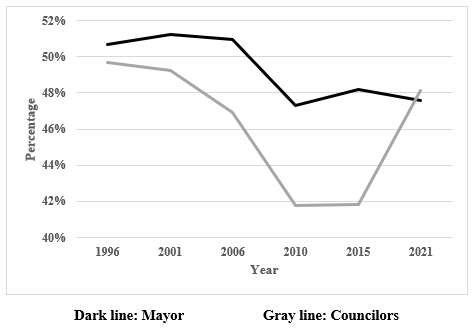

Another aspect to consider is the unblocking of lists. It is already a reality. As many analysts anticipated, the unblocking could favor the big parties and we saw that in the municipal elections of 2021. Let’s see what percentage of votes the ANR had for its candidates for mayor and for its lists of councilmen:

Figure 4: Percentage of ANR votes (over valid votes) in municipal elections since 1996. Votes for mayors and list of councilors.

Historically, the ANR had fewer votes for its list of councilmen than for its candidacies for mayors. If we look at the data of the general elections, the votes for president and for the lists of senators, representatives and departmental councilors show a similar pattern: the votes for the lists are lower than for the candidacy for president.

However, in the 2021 election that did not happen, and the ANR made an excellent choice for councilors. Why? One of the arguments that could explain is that previously, the ANR voter who was not satisfied with the first places on their list looked for an alternative. With the unblocking, there is no order and one can vote for the one he likes. While there may be several unpresentable candidates on their list, there will be at least one that they like. Whether this is the reason or not, it is irrelevant to what we are arguing. Seeing what happened in the municipal elections of 2021, it is a reality that the ANR will increase its senators and deputies in 2023 and, if there is no strategic response from the opposition, the probability of an ANR majority in both chambers is high.

What is left for the opposition to do? Certainly, to have fewer lists. Here it is necessary to take advantage of the unblocking, which can facilitate the union. Let me give an example: the Patria Querida party in its best election (2003) won seven seats in the senate. Does it need to present forty-five candidates? No. Let’s suppose that in a miraculous election it can get fifteen senators. Now, how many can the Encuentro Nacional Party get? Maybe five, in an also miraculous election. Soledad Núñez’s people, with a lot of luck, eight. Hagamos? Maybe three. Estimating from above, we still do not have forty-five, so there are places for others.

Then, all these parties (which are not so different ideologically and that is why I gave them as an example) could make a list together and run all together. Maybe the Concertation will not be able to have a single list, but one more left-wing, another one more right-wing and maybe the PLRA on its one, which is not unreasonable. What is the use of looking for people to fill a list if other candidates with possibilities from other parties can be added? That is the good thing about the unblocking, and the opposition should be practical and take advantage of it.

If the Concertation has only three or four lists (but the fewer the better), it will be a big step. The example of the municipal elections of 2021 should serve as a lesson, if not, let us see what happened to the progressive sector that made a process of “de-concertation” (the parties of the Frente Guasú presented two lists, and other progressives went to other lists) in Asunción. It went from four councilors to none.

Cover image: ABC Color