United or divided? the opposition’s dilemmas for the Senate. Effects of closed and unblocked lists on senatorial candidacies

By Fernando Martínez Escobar

Among the political forces that make up the recently created Concertation, there are basically two positions in relation to the conformation of the lists for the Senate; one seeks to present a unified list and the other to maintain its own lists.

What should the political parties and forces do: should they go together on a single list or should they present different lists?

A priori, the effect of closed and unblocked lists with preferential voting in the 2021 municipal elections in Paraguay allowed us to observe that the greater the internal competition among the members of the same political list, the greater the number of seats to which the list gains access. That is to say, the more votes each individual candidate brings, in competition against his or her own list partner, the greater the chances that a greater number of members of the list he or she represents will enter.

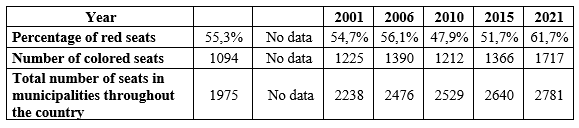

In fact, in last year’s elections, with the new electoral rules implemented for the first time, the Colorado Party achieved the highest percentage of municipal council seats in its history. Table 1 shows how the ANR achieved 62% of the total seats available at the national level, surpassing by 10 points the percentage achieved in the 2015 municipal elections.

Table 1: NRA Councilors at the country level

Source: Fernando Martínez Escobar with data from TSJE and Arditi Benajamin (1992).

One hypothesis to explain the increase in seats for the ANR is that each person chooses a candidate from the list, but at the same time chooses the whole party or list, so the voter may not like one or several candidates on the list, but since his or her candidate is on that list, he or she votes for his or her candidate and, in doing so, also votes, whether he or she wants to or not, for the whole list, that is, for the candidate or candidates he or she did not want.

Therefore, paradoxically, containing or maintaining, in the same list, opposing electoral offers can be electorally positive for the list. In terms of electoral strategy, internal competition is a collective and individual need at the same time.

Collective because the seats (or number of seats) are distributed proportionally based on the number of votes obtained; and individual because the initial order of the list is reordered based on the votes of each candidate. In other words, each candidate has the incentive to differentiate himself or herself from his or her running mate by bringing different proposals and focusing his or her campaign on groups or niches large enough to enable him or her to secure a seat.

In turn, the need for differentiation causes the electoral system to encourage the flight from the center or from spaces already populated by other candidacies and promotes an electoral political behavior that encourages candidacies to seek territories that are not well inhabited or, in other words, underrepresented.

In this regard, and given the need for differentiation, the new electoral rules are also an opportunity for demands that have so far failed to take root in the representative and institutional electoral field to win seats. For example, it is an opportunity for candidates who promote laws against all forms of discrimination, gender policies or equal marriage to gather behind their candidacies a significant number of people to gain access to national seats or, on the contrary, it is also an incentive for candidates to radicalize their proposals, seeking the vote of more right-leaning spaces. In fact, some candidates, such as Enrique Riera, have already begun to direct their speeches towards these sectors. In this sense, Riera does not mind being politically correct or receiving blows from sectors more located towards the political center, if he can dispute the leadership of sectors that seek more conservative measures.

Now, from what has been exposed so far, regarding the unification of lists for the Senate and its effects, the NRA does not seem to face many problems and, even if we take as a background the results of the municipal elections, it is possible to foresee that in the Senate elections its numbers could also improve, based on its strong internal competition and the multiplicity of its proposals. On the other hand, on the other hand, the opposition faces dilemmas of contradictory electoral incentives when unifying its lists for the Senate. Why?

Because the opposition parties are in positions of strength that are often diametrically opposed, and this makes their strategic calculations also vary. It is not the same to form a unified list for parties that already have representation in the Senate Chamber, as it is for parties that did not have representation in 2018, or for movements that are being formed in view of the 2023 elections. It is not even the same for the three opposition parties with the most seats in the Senate: the PLRA, the Frente Guasu or Patria Querida.

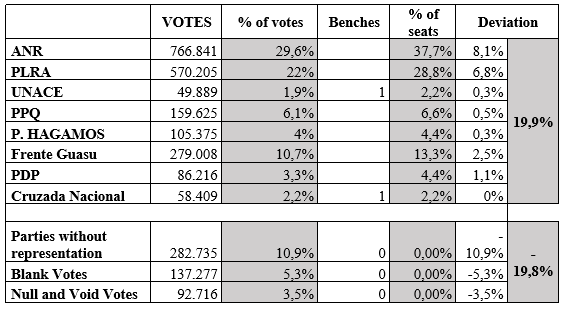

In the Senate, the great fragmentation of electoral proposals (of political parties or movements) favored parties with parliamentary representation (and not just the ANR or the PLRA). In the 2018 elections, there were 29 lists for the Senate, of which, 8 lists achieved representation. Table 2 shows how 20% of the votes cast went unrepresented; of these votes, 11% voted for political forces that did not obtain any representation. If the lists of these unrepresented parties had been unified, they would have obtained 5 seats. Blank votes would have obtained 2 seats with 5%, null votes 1 seat with 3%. Finally, UNACE would have been left without seats.

In addition, in the 2018 elections, the 20% of votes without representation did not vanish, but contributed to the parties with representation having a higher percentage of seats than votes in relation to the total participation. Thus, the ANR obtained 3 more seats, the PLRA 2 more seats, the Frente Guasu 1, the PDP 1 and the Hagamos Party 1 more. In summary, the 8 political forces were benefited with a percentage overrepresentation over the total participation.

Table 2: Percentage of votes versus percentage of seats by party

Source: Fernando Martínez Escobar with data from TSJE

Looking at the action of the political forces from this perspective, the unification of the Senate lists into a single list could very well take these elements as part of the negotiation, since, while a unified opposition list may increase the number of Senate seats for the opposition, at the same time the larger political forces within the Concertation will not want to lose the number of seats already obtained in 2018.

the new electoral rules are also an opportunity for demands that have so far failed to take root in the representative and institutional electoral field to win seats. For example, it is an opportunity for candidates who promote laws against all forms of discrimination, gender policies or equal marriage to gather behind their candidacies a significant number of people to gain access to national seats or, on the contrary, it is also an incentive for candidates to radicalize their proposals, seeking the vote of more right-leaning spaces.

In this sense, the PLRA, being the second largest force in the country, in general benefits in each of the elections without the need to unify the lists, while the Frente Guasu, which also obtained an overrepresentation in 2018, counts in its ranks with a super elector such as Fernando Lugo (at least so far), who will therefore receive enough votes for the Frente Guasu to access a few seats. On the other hand, if the Frente Guasu goes within a unified list, Lugo’s votes will also extend to other political forces that integrate the list and not only the Frente Guasu.

On the other hand, other political forces (such as Patria Querida) have already announced that they will present their own list, while Katya González (Encuentro Nacional), Soledad Núñez, the Hagamos Party and Despertar have just unified their lists for Congress to be called “Alianza Encuentro Nacional”. This decision is in accordance with their resources of less institutional political power and therefore closer to the approach of unification of lists, explained at the beginning of this article.

So: United or divided?

Cover image: El Mundo.es