By Rodrigo Ibarrola

The low voting participation of young people under 30 is frequently mentioned as one of the reasons why electoral results always end up favoring party structures. In this hypothesis, it is stated -almost mystically- that if young people were to achieve a higher level of participation, professional politicians would be displaced. This is not a belief that only exists in our country. Neither is the lower relative participation of the young population in elections. On the contrary, it is a common phenomenon that occurs both in democracies that we would consider well-grounded and in those that are not.

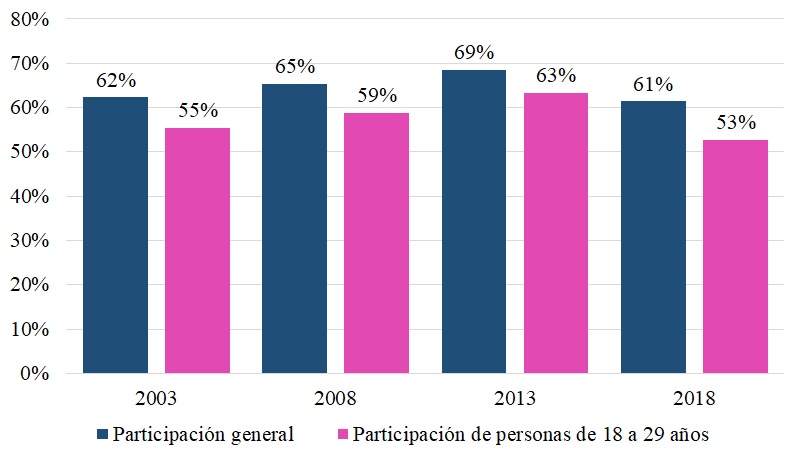

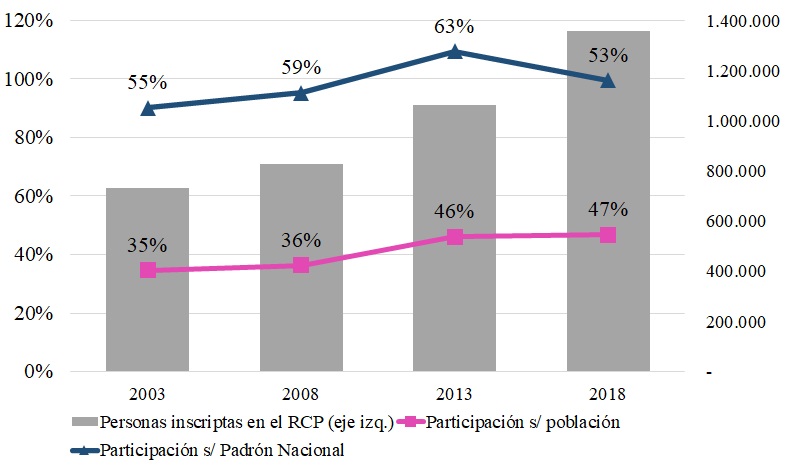

It is true that if we look at the 18 to 29 age group, we will observe that people of that age present a lower participation compared to the general participation (Graph 1). However, in the overall, it is the age group that contributes the highest number of votes. So, the quick answer to the question of whether young people vote is: yes, but there are still issues to consider. For example, what do we consider low participation? Assuming as an ideal the overall participation rate, the level of participation of young people is clearly below average.

One might think that the inhabitants of rich and highly democratic countries are more likely to vote. Certainly, this is true in countries such as Sweden, Denmark, the Netherlands, South Korea (with turnout rates above 76% in their last elections). However, there are also countries such as Switzerland, New Zealand, Finland, Chile, United Kingdom (with turnout below 52%). Paraguay is located with 53%. Therefore, as has been said, low turnout is not a phenomenon exclusive to Paraguayans. Therefore, it is worth asking ourselves -beyond the fact that it is morally and ethically desirable- if the quality of democracy (or alternation) really depends or not on the youth vote. A difficult question to answer, and one that requires another type of analysis.

Graph 1. Participation of 18- to -29 year old’s in general elections, 2003-2018. As a percentage of 18- to 29-year-olds enrolled in the RCP

Source: Own, with data from the Superior Court of Electoral Justice (TSJE).

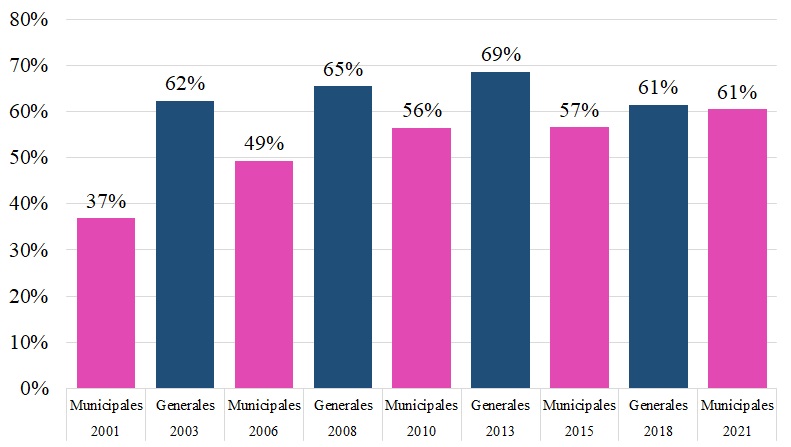

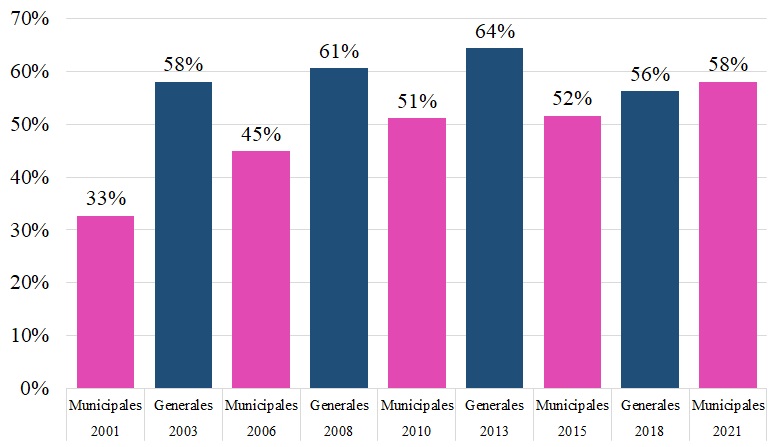

On the other hand, it is noteworthy that electoral participation has been increasing over time (along with the registered population). This phenomenon is registered in both general and municipal elections (Figure 2), although a cyclical behavior can be glimpsed, since in the latter -generally- lower levels are registered than in the general elections.

Graph 2.Total electoral participation in general and municipal elections, 2001-2021. As a percentage of total number of persons registered in the RCP

Source: Own, with data from the Superior Court of Electoral Justice (TSJE).

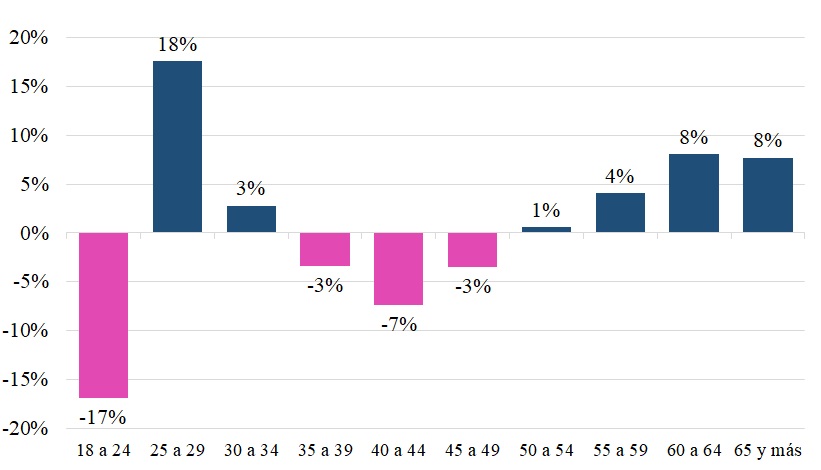

Comparing the participation recorded in the 2003 and 2018 elections, and disaggregating by age, we can see that the growth in participation has not been similar in all age groups. Figure 3 shows the breakdown in ten categories, where the 18 to 24 years old age group is the one that registered the highest decrease, with a negative variation of 17%.

Graph 3. Variation in voter turnout between 2003 and 2018 general elections by age. As a percentage of persons registered in the RCP by age group

Source: Own, with data from the Superior Court of Electoral Justice (TSJE).

But there is a detail to consider: in 2012, automatic registration was implemented for those young people who turned 18 years old, which affected the participation rate in the under-30 age group. Given that automatic registration operates regardless of the intention of young people to vote or not, a lower turnout was to be expected, as the base of eligible voters increased disproportionately.

What does result is classroom teaching practices that allow young people to debate and learn about contemporary political issues. Active involvement in these issues before the age of 18 increases the likelihood of voting. It also allows young people to increase their knowledge and develop skills such as, for example, communicating effectively with someone who has different views, developing a young person’s confidence in their own ability to participate.

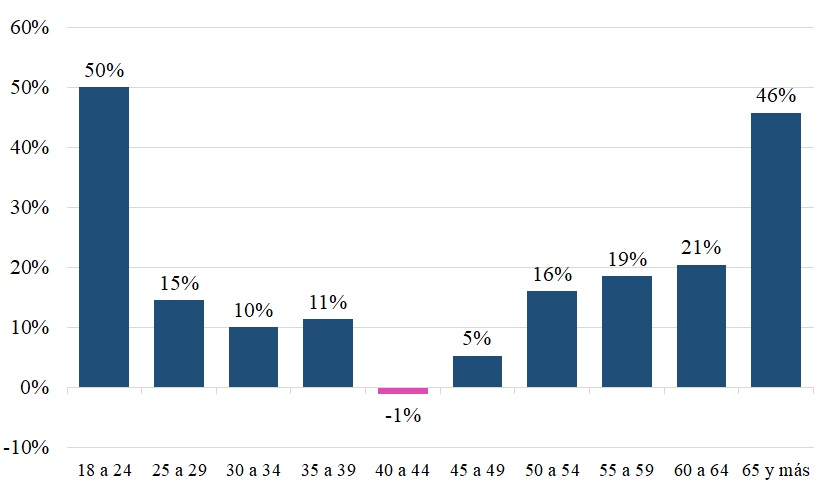

A simple way to correct this distortion is to calculate participation in relation to the general population of each age group for each given year and not in relation to those registered in the national census, that is, to adjust it by population, since we know that not all the population is registered in the Permanent Civic Registry (RCP). Once this adjustment is made (Graph 4), the youngest age group was the one with the highest increase in electoral participation. This is explained by the fact that the increase in RCP registration is significantly correlated with the increase in electoral participation in this age group. In fact, the electoral participation of young people is a direct result of the number of young people registered. The causes have to do with the elimination of bureaucratic barriers for registration and, therefore, also for participation.

Figure 4. Variation in voter turnout between 2003 and 2018 general elections by age. As a percentage of the population by age group

Source: Prepared by the authors with data from the Superior Court of Electoral Justice (TSJE) and the National Statistics Institute (INE).

Returning to people under 30, in Figure 5, we can see that, as the number of registered voters rises, the line of electoral participation calculated on population also rises steadily, unlike the line calculated from the national census, which suffers a drop after 2013. With this we verify that the “real” participation of young people, far from decreasing, has increased steadily from 2003 onwards. Additionally, it is also observed that both lines tend to converge because the proportion of registered persons in relation to the population of that age has gone from 60% in 2001 to 94% in 2021.

Figure 5. Voter turnout and number of registered voters aged 18 to 29 years old. As a percentage of RCP enrollees and population

Source: Prepared by the authors with data from the Superior Court of Electoral Justice (TSJE) and the National Statistics Institute (INE).

Source: Prepared by the authors with data from the Superior Court of Electoral Justice (TSJE) and the National Statistics Institute (INE).

A not minor detail is that in 2021, thanks to the competition among candidates in the lists caused by the unblocking, a trend that had been constant since 2001 has been broken. For the first time, youth participation in municipal elections exceeded the participation rate of the previous general election (Figure 6). This occurs regardless of whether the reference taken is the national census or the population. This phenomenon raises hopes of observing a high youth participation in next year’s general elections, a very important aspect since young people make up 31% of the electorate (1,457,822 voters), of which 53% are independent, according to the national electoral roll of October 2021.

Figure 6. Electoral participation of people aged between 18 and 29. As a percentage of population

Source: Prepared by the authors with data from the Superior Court of Electoral Justice (TSJE) and the National Statistics Institute (INE).

The above allows us to refute the idea that younger voters, either because of disinterest or apathy, are voting less and less. Although this group continues to have a lower-than-average participation, it is worth noting that it has been the one with the greatest increase, significantly narrowing the participation gaps.

What can be done to encourage voting? Some of it has already been done. With automatic registration, the barriers for registration have been removed, obstacles that disproportionately affect young people, since the available evidence suggests that they are the most likely to desist from voting in the face of these inconveniences. With that hurdle removed, many are now able to do so. And they do, as the evidence and the growing numbers in our country show, after the implementation of automatic registration.

But ease of registration is not everything. Another relevant issue -with a long-term effect on the promotion of suffrage- is civic education. But not as it is implemented today, reduced to a mere memorization exercise of historical facts, civic norms, and government rules. Existing research shows that this approach simply does not yield greater civic engagement. What does result is classroom teaching practices that allow young people to debate and learn about contemporary political issues. Active involvement in these issues before the age of 18 increases the likelihood of voting. It also allows young people to increase their knowledge and develop skills such as, for example, communicating effectively with someone who has different views, developing a young person’s confidence in their own ability to participate.

We have then that combining automatic registration with a teaching method that facilitates the civic participation of young people from the classroom can be valuable for later participation. After all, voting is a habit that must be encouraged and, like any routine, the most difficult moments are the initial ones.

Cover image: New York Times