By Marcos Pérez Talia

In a recent article, we recovered the argument of Pierre Rosanvallon who examined the principles of legitimacy of democratic governments. According to the French sociologist, throughout the twentieth century a democratic system of dual legitimacy was established, one of input (electoral) and another of results (public administration). In this article, after a brief theoretical debate, we explore electoral legitimacy in Paraguay and show data suggesting that, at least since 2018, there has been an erosion of trust in electoral democracy. In the present article we will investigate the second legitimacy, that of results.

Rosanvallon’s main theoretical argument is that, at the end of the 19th century, popular election became the only means of access to representative office and, to a certain extent, the natural expression of popular sovereignty. Subsequently, faced with the crisis of representation at the beginning of the 20th century, because of the distancing between the representatives and the people, public administration was consolidated. The State had to transform itself from a mere guardian of liberties and property to one that offered basic public services such as health, education, housing and higher levels of infrastructure.

Focusing on the Paraguayan case, the most remarkable feature of its democratic system was the electoral dimension, which since the 1996 municipal elections fully conformed to Robert Dahl‘s postulates of procedural (or polyarchic) democracy. Unfortunately, a deterioration of electoral legitimacy emerged after the mishandling of the 2018 general elections. In turn, the legitimacy of results never managed to reach desirable levels in Paraguayan democracy, whose shortcomings date back a long time, as we will see below.

Several academic papers have previously studied Paraguay’s state responsiveness. Mikel Barreda and Marc Bou published, in 2010, an academic article that measured the quality of Paraguayan democracy. One of its analytical dimensions was responsiveness, that is, the government’s capacity to respond to the preferences of its citizens, whose result was perceived as very weak, with scores that place the country in the last positions in Latin America. In another academic text, Diego Abente Brun also analyzed the quality of Paraguayan democracy, although in line with (low) statehood. His findings revealed the persistence of a weak State not only as an apparatus but also as a State-for-the-nation. On the one hand, he observed a constant growth in the size of the State (also in revenue and expenditure) but, on the other hand, it continues to have an asset like (patrimony) component (in Max Weber‘s terms), governed by businessmen and politicians who colonize the State. All this, ultimately, causes the poor performance of the system.

Responsiveness is a fundamental characteristic of any democracy. The process is somewhat complex since, ideally, it suggests a three-step path where citizens structure and order their preferences, which are then institutionally aggregated by parties into the political system and finally become public policy. The complexity is even more acute when it comes to evaluating the performance of responsiveness, since there are no clear and precise indicators, nor is there a consensus in the academic world. To measure the Paraguayan case, we will opt for three traditional indicators whose statistical data are available in the LAPOP and Latinobarómetro databases.

The first classic indicator is the level of “satisfaction with democracy”. Although it may have limitations, since the opinion expressed therein could be associated, rather than with democracy, with the functioning of certain institutions, or even with the approval (or rejection) of the government’s performance. Despite these risks, the indicator “satisfaction with democracy” is capable of providing an initial overview of the functioning of the political system.

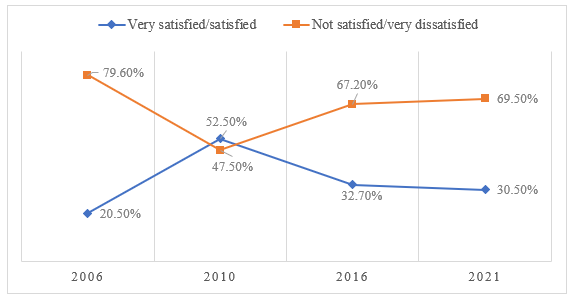

Figure I. Satisfaction with democracy

Source: LAPOP databases

The data show a worrying result of dissatisfaction with democracy, except in 2010 when the Patriotic Alliance for Change governed, with Fernando Lugo in the presidency. The last measurement of 2021, which gave only 30.5% satisfaction, is well below the average for Latin America that year, which stood at 43%.

The second variable that can shed light is whether “basic rights are protected”, with responses ranging from 1 to 7, where 1 means less protection and 7 means more protection. Figure II below shows the mean number of responses for each presidential term.

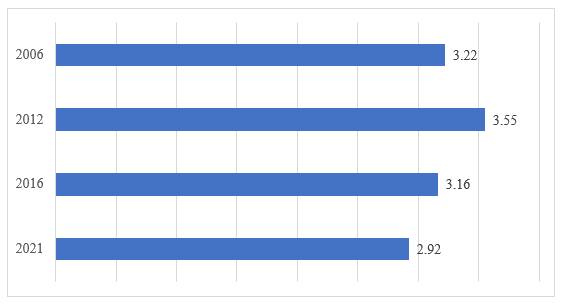

Figure II. Are basic rights protected?

Source: LAPOP databases

Once again, the results show a downward trend. With 7 being the highest response, the average for each government is less than half of the highest response. Except, once again, during the government of the Patriotic Alliance for Change (2008-13), where the result was slightly above half (3.55%).

Finally, Figure III shows the responses on the perception of “the functioning of the economy” during the last five presidential administrations.

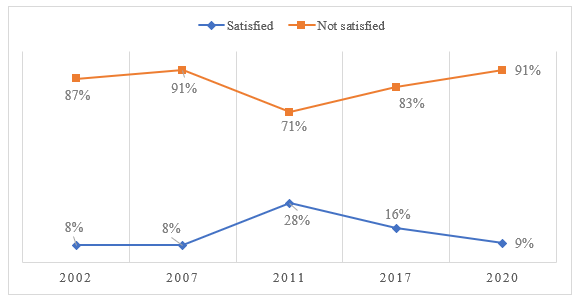

Graph III. Satisfaction with the functioning of the economy

Source: Latinobarómetro databases

Dissatisfaction is very high and sustained over time, while satisfaction is very low. During the governments of Luis González Machi (1999-2003), Nicanor Duarte Frutos (2003-08) and Mario Abdo Benítez (2018-23) satisfaction did not even exceed 10%. The best results were obtained in the government of Fernando Lugo, with 27.6%, and that of Horacio Cartes, with 15.9%.

Responsiveness is a fundamental characteristic of any democracy. The process is somewhat complex since, ideally, it suggests a three-step path where citizens structure and order their preferences, which are then institutionally aggregated by parties into the political system and finally become public policy.

The two sources of democratic legitimacy in Paraguay are under question. But this is no longer a mere transitory situation that can be overcome by means of some simple institutional surgery. A profound structural innovation of the political system is also required.

It is urgent to recover confidence in electoral democracy, but it is even more urgent to strengthen the democracy of results. For a long time, all measurements of political culture (both LAPOP and Latinobarómetro) have been calling attention to the dissatisfaction of Paraguayan citizens with democracy and the performance of its institutions.

The general elections of 2023 could be a common place to start, once and for all, the changes that cannot be postponed.

Cover image: Marce.af / www.revistaciendiascinep.com