By Rodrigo Ibarrola

After months of uncertainty, the Executive Power finally vetoed completely the Law that would have allowed service providers to deduct Value Added Tax (VAT) on purchases of food products, clothing and other items that would not usually be deductible under the current law, unless they are related to the service provided. On the other hand, it issued a decree allowing a partial deduction of up to 30%. The bill returns to Congress, where both chambers must decide whether to accept the veto or ratify its initial sanction. Deputies accepted the veto, only the ratification of the Senate remains.

Judging by the approach of the press, as well as by the actors addressed, it is possible to infer that most of the media have adopted a favorable perspective towards the law. So much so that it was very unusual to find opposing voices in the daily interviews. This asymmetrical coverage of the positions gives substance to a proposal that, in principle, seems reasonable, but is not so when analyzed in detail.

The explanatory memorandum of the law mentions that the non-inclusion of supermarket receipts among the deductible expenses “constitutes a blunt blow to the working class”, a brief mention is made of the promotion of smuggling and there is no mention at all of informality.

This point is inaccurate: workers total some 3.6 million people, while the potential beneficiaries of this law are only some 273 thousand (of which only 65 thousand are taxed, according to the Treasury). It is worth asking whether the remaining ones are not considered workers, since the parliamentary initiative would deprive this group, which represents 93% of the workers, of the benefit, thus threatening tax equity. This undeniable fact -already pointed out by the Ministry of Finance- has caused private promoters of this law (such as Alberto Sborovski, of the Paraguayan Chamber of Supermarkets, CAPASU, and the analyst Amilcar Ferreira) to change their arguments towards the fight against informality.

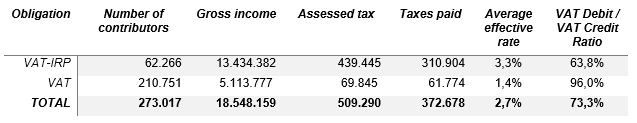

Table 1. General VAT taxpayers for personal services, 2021 – In millions of guaraníes

Source: Subsecretaría de Estado de Tributación.

Regarding Ferreira, on November 1, in the program En Contexto, hosted by Luis Bareiro, he mentioned the Uruguayan case as a successful example, without expressing what he means by “successful”. Therefore, it is pertinent to make some comments on the mentioned case.

increasing the deductibility of VAT as an instrument to promote formality has no empirical basis. It will generate tax inequity by granting benefits to higher income sectors (the informal sector earns approximately half the income of the formal sector and still pays taxes), it will have no impact on informality, and the multiplier effect will not compensate for the decrease in tax collection.

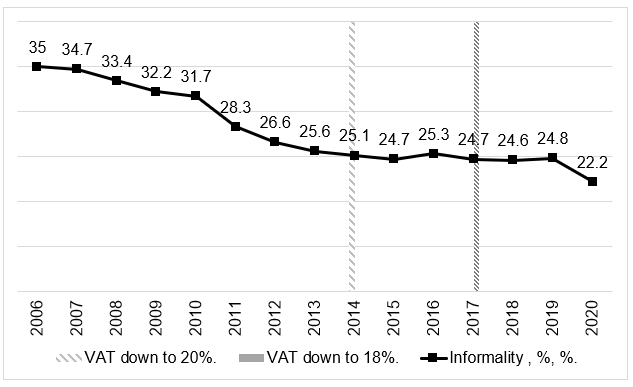

First, the Uruguayan policy consisted of modifying the nominal rate, not the deductibility of the settlement; second, the objective was to foster financial inclusion, not to reduce informality. Indeed, in 2014, Uruguay reduced the nominal VAT rate from 22% to 20%. Then, in 2017, it lowered it again to 18%. Obviously, such a measure had no effect on informality, which can be easily noticed graphically.

Figure 1. Labor informality in Uruguay, 2006-2020, in percentages

Source: Own, with data from Observatorio Territorio Uruguay.

This is logical, since, basically, the Uruguayan government’s aim was to encourage the use of electronic means of payment, through an incentive in the VAT rate, i.e., only applicable to those transactions, and thus promote financial inclusion. In fact, the regulation itself is called “Financial Inclusion Law“. It is true, it was a success, the percentage of people over 15 years old with a bank account went from 45% in 2014 to 64% in 2017, to stand at 74% in 2021.

Furthermore, when we talk about informality we can refer -in most cases- to the proportion of workers who do not contribute to social security (in which case it is not clear how the VAT rate could affect it) or to the informal economy, which is the value of economic activity that is not registered, and this can be carried out by formal actors, such as, for example, smuggling or drug trafficking using legal facades.

About the reduction of labor informality in Uruguay, this was the result of a series of policies adopted since 2005 that included the implementation of collective wage bargaining supervised by the State, a broad (non-sectoral) tax reform, incentives for productive investment through the exemption of corporate income tax and the incorporation of the concept of job quality. In addition, with sustained economic growth, fiscal space was created for the implementation of social security and employment plans, countercyclical fiscal policy, social protection with income transfers to the most disadvantaged sectors, among others. In short, the reduction of informality was obtained thanks to a high and sustained economic growth, aligned with a series of policies promoting employment generation and adequate protection. And not through VAT.

On the other hand, in view of the possible collection loss of about 100 million dollars, estimated by the Undersecretary of State for Taxation (SET), in case this measure is implemented, both Ferreira and Sborovski argued that the savings generated to consumers would generate a “boom” in consumption that would compensate for the resigned amount. This idea is rooted in economic theory and is known as the “income effect”, which basically stipulates that allowing the VAT deduction puts money in consumers’ pockets, and they, in turn, make additional purchases, which stimulates spending and economic activity.

Under this hypothesis, and assuming that all purchases to be deducted are taxed at a rate of 10%, a boost would be needed such that the overall increase in spending -within the formal economy- would be about US$1 billion (2.5% of GDP), i.e., a multiplier effect of 10 times what is deducted. However, several of the goods affected already have the reduced rate of 5%, so the multiplier effect should certainly be greater than 10. Waiting for a 10-fold increase in spending, when the empirical evidence places it at around 2.7, is totally unsubstantiated.

Informality is the cause of a lack of economic and institutional development. It exists because it offers flexibility for employment in economies constrained by low labor and business productivity, and by a State that is inefficient in the provision of services and ineffective in its regulatory and tax burden. Given these conditions, if there were no informality, there would be greater unemployment, poverty, conflict, and crime.

The conclusion we can draw from this is that increasing the deductibility of VAT as an instrument to promote formality has no empirical basis. It will generate tax inequity by granting benefits to higher income sectors (the informal sector earns approximately half the income of the formal sector and still pays taxes), it will have no impact on informality, and the multiplier effect will not compensate for the decrease in tax collection. Although inequities already exist, the right thing to do would be to address them comprehensively and not in a sectoral manner with initiatives that further undermine the already low tax burden and, above all -but not least- to use reasonable arguments in the discussion.

Cover image: Agencia IP