By Jorge Rolón Luna*

The term “narco-state” (NS) has become common when it comes to designating countries facing serious problems such as violence, corruption, criminal groups allegedly controlling territories, and where sectors of the political class, state bureaucracy and security forces are given over to the “narco”. The Paraguayan State, where some of these issues have been observed with certain clarity for some time now, has not escaped being characterized in this way. What happens is that this view entails a conceptual mistake that leads to a wrong diagnosis of the problem and, therefore, to the insistence on supposed solutions that do not even alter the situation. In a series of articles, I will first present the background of this mistaken conceptualization (originated in the use of a Weberian matrix of analysis of the State); second, I will advance with alternative conceptualizations that are much more precise to analyze the relationship between the State and drug trafficking; and, finally, I will conclude with a third article that illustrates why Paraguay is, more than a narco-state, a State that runs a multiplicity of illicit businesses.

An NS is one that is normally considered to have one or two fundamental roles: to produce some type of illegal drug or to serve as a transit corridor for illegal drugs. Several countries have been identified in these roles, such as Colombia, Mexico, Burma or Afghanistan. These accusations have come from specialized international organizations of the UN (UNOCD), heads of state, politicians, journalists and even academics. Given that Paraguay occupies a preponderant place in the production and transit of drugs, it is not surprising that several sectors qualify Paraguay as a NS. This has been seen in the media, civil society, foreign diplomacy, international organizations and even in the academia.

These views are inconsistent because they clash with the conceptual matrix derived from Max Weber’s work on the State. Weber defines the State as “that human community which, within a given territory (territory is the distinctive element), claims (successfully) for itself the monopoly of legitimate physical violence”. From this perspective, the thesis of Paraguay as “an NS” leads one to think that the “narco” controls parts of the territory, imposing its violence and surpassing the capacity of the public apparatus itself, which would have given in to its insurmountable power, placing its structure and functions at the service of ends different to those of a modern State.

Neither NS nor “absence of the state.” The Paraguayan state is not an entity that is directly involved in the drug trafficking business, although at times it may seem so, nor is the absence of the state taken advantage of by criminal groups to prosper in this supposed power vacuum. In reality, what is evident is a State that is very present to regulate, protect and profit from a business that is functional to the maintenance of the political system, on the one hand; and an absence of the rule of law, on the other.

The problem is that, according to Weber, for non-state organizations to control territory they can only do so to the extent that the state “grants them the right to physical violence. If those who control territory in Paraguay – drug traffickers, in this case – do so outside the State, we would be dealing with a case of two-headed power, a “duopoly of violence”, contrary to the Weberian concept of “monopoly of legitimate violence”.

For Weber, the monopoly of violence is the distinctive feature of a state. This is based on three reasons: the preservation of state unity vis-à-vis the outside world; the eventual need to expand the country’s resources and territory by means of war; state force as a permanent threat to those who seek to change the organization of society (internal peace). In other words, a State that is surpassed by groups, factions, or entities of any kind in the application, possession and monopoly of legitimate force lacks one of its fundamental qualities. Without being the sole source of the right to violence, the State as such would not exist and would enter anarchy.

For Weber, the legitimate exercise of violence is the most important attribute of the State, even in ontological terms. Without this essential attribute there is neither territory, nor population, nor legal order; there is no State. What allows the political existence of the State is its superiority over any existing power in a given territory, which in turn allows it to maintain itself over time.

From this conceptual framework, it is difficult to explain how criminal groups dedicated to drug trafficking embody the State itself. How they have constituted a parallel state by imposing their legal order, monopolizing the use of legitimate force in a territory, to turn it into an organization dedicated entirely to drug trafficking. To date, there is no empirical evidence of such a thing. What has been proven is that the State has always controlled the business of prohibited substances, since its beginnings in the late 1960s, and that this model has not been substantially altered.

Seen in this light, an eventual surrender of the Paraguayan State – with the loss, reduction, limitation, or serious contestation against its will of the monopoly on the use of force – must necessarily be understood as the non-existence or replacement of the State as an entity. This is the view that lies behind the also widespread idea that, with the failure of the Paraguayan State in its capacity to monopolize violence against drug trafficking groups, what we have is an “absent State”.

It is very common to find politicians, communicators and even academics who argue that this supposed absence of the state explains the rise of criminal groups in certain areas of the country. Something that, incidentally, has been called into question by Carlos Peris with Sarah Cerna and another by Sonia Alda Mejías, in which data in hand refutes this vision, repeated ad nauseam in the case of Paraguay.

Neither NS nor “absence of the state.” The Paraguayan state is not an entity that is directly involved in the drug trafficking business, although at times it may seem so, nor is the absence of the state taken advantage of by criminal groups to prosper in this supposed power vacuum. In reality, what is evident is a State that is very present to regulate, protect and profit from a business that is functional to the maintenance of the political system, on the one hand; and an absence of the rule of law, on the other.

*Researcher. Former director of the Observatory of Coexistence and Citizen Security of the Ministry of the Interior.

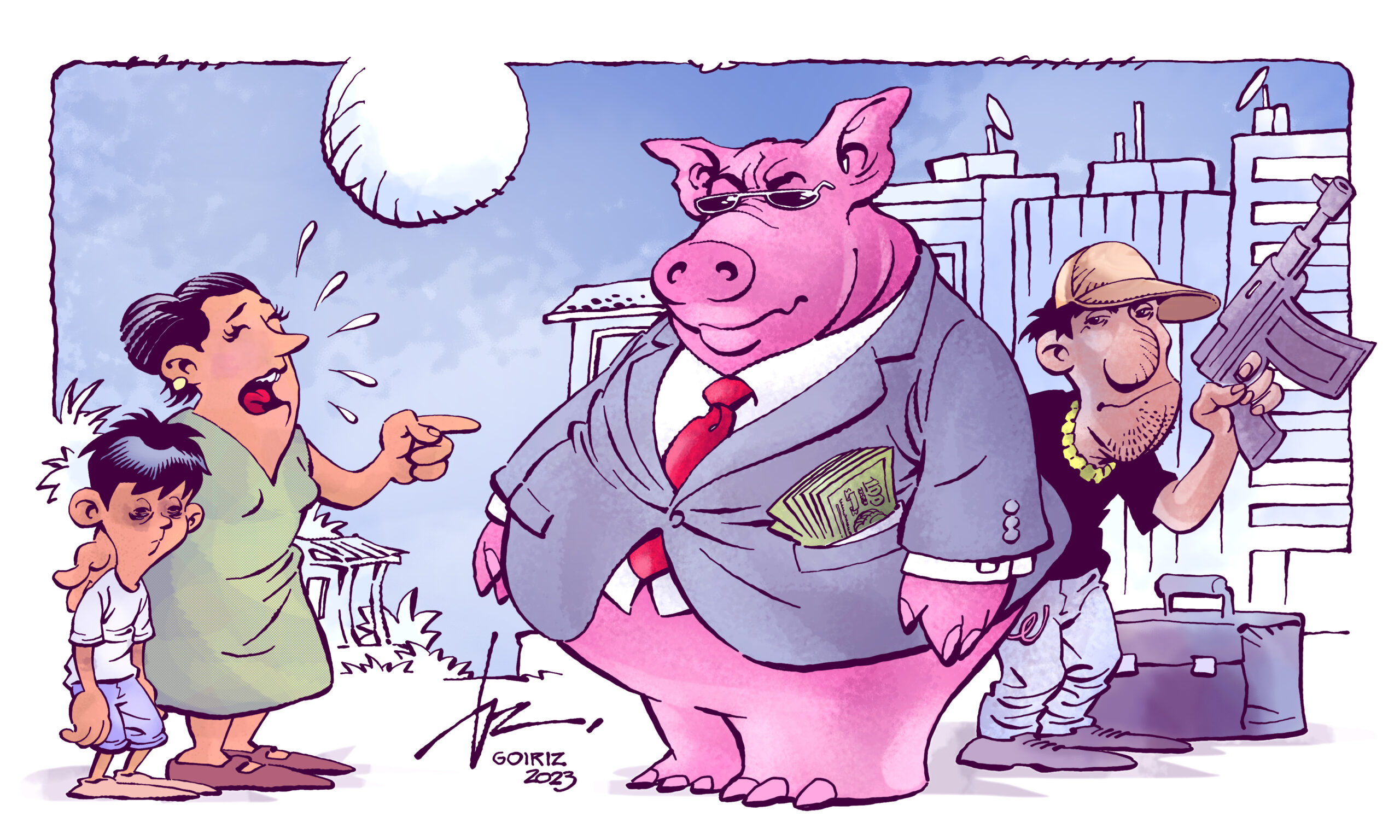

Cover image: Roberto Goiriz