By Javier Lassalle

High oil prices and public policy attempts to mitigate the effects of the rise put the fuel sector under the spotlight. Although the policy measures (such as the stabilization fund or the subsidy to Petropar) sought a temporary solution, in this article I would like to analyze a structural distortion that keeps fuel prices high, generates profit for private entities by about USD 80 million per year and leads to a disproportionate number of service stations in the country.

The data show that Paraguay has the highest number of service stations per person in South America. Paraguay has more service stations than Chile, for example, a country with a population of 19 million and a higher average income than Paraguay.

In the absence of a conclusive explanation for this phenomenon, the possibility has been raised that this responds to a non-financial issue, specifically money laundering. Under that assumption, service stations would not necessarily be generating profits, since they would be used to launder their owners’ dirty money. I do not have elements to rule out this possibility, but in this article I want to show that there are financial reasons for the high number of service stations.

First, let’s look at how the fuel market in Paraguay actually works. After several regulatory changes, the imports and pricing of all types of fuels has been free since July 2018.

The high number of service stations could be linked to Petropar’s inefficient cost structure. Part of this inefficiency is in the “intergovernmental contribution”, which can (and we believe should) be transferred to the selective excise tax for all fuel companies. With this exchange of intergovernmental contribution for an increase in the selective excise tax, the government keeps its collection fixed and reduces the cost to Petropar, which would allow it to reduce its prices.

Although the market is competitive in theory, the facts show that it is an oligopoly. Although different distributors import from different suppliers, on different dates at different prices and exchange rate values, they all sell at exactly the same price. There is usually not a guarani of difference between one gas station and another (except for those resulting from credit card promotions). This is a clear sign of collusion, typical of an oligopoly.

In addition to formal free competition, the other important feature of the fuel market is the existence of a state-owned company. Petropar (the state-owned company) acts as a sort of regulator in this free market. Whenever Petropar modifies its prices, private companies follow.

The fact that private companies decide to offer their products at the same price as Petropar and continue to add gas stations would indicate that private companies are at ease with Petropar’s price, probably because they have lower costs and, therefore, high profits. Furthermore, by following Petropar’s price, their prices are justified since the state-owned company is not able to improve the prices of the private companies.

Why does Petropar have higher costs?

There are several potential reasons that are already under discussion (such as intermediaries or the requirement of sworn statements from suppliers, or simply corruption), but I would like to focus on one that has a quick solution.

The general budget of the nation establishes that Petropar (as well as other state entities) must make an “intergovernmental contribution” to the treasury. In the year 2021, for example, it was Gs. 110,000,000,000,000 (about USD 16 million). That same year Petropar imported 451.9 million liters of diesel oil and fuel. In other words, the annual intergovernmental contribution is equivalent to the State imposing an extra tax on Petropar of Gs. 243.4 per liter. It is equivalent in the sense that the revenue for the Treasury would have been the same with the intergovernmental contribution or with an extra tax on Petropar of Gs. 243.4 per liter. Now, the obvious question: why does this extra tax per liter apply only to Petropar and not to private companies?

I don’t think there is any logical explanation today, but I understand that it could have been a mistake that was dragged over by the change in the rules of the game. In the past Petropar had a monopoly on the importation of some fuels (especially Diesel oil). This allowed Petropar to make extraordinary profits and thus putting a lump sum tax on Petropar (as is the “intergovernmental contribution”) had some justification. Since 2018, with the end of the monopoly, the contribution no longer has any justification. This contribution for Petropar had been eliminated in the 2017 budget and returned as of 2019, just when the monopoly ended.

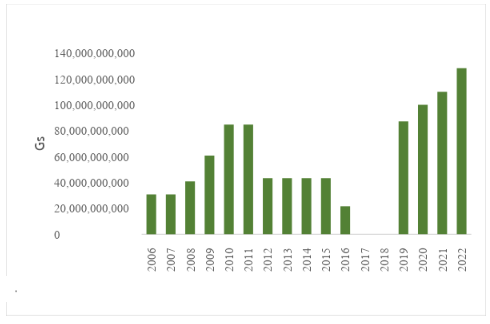

Figure 1: Petropar’s Intergovernmental Contribution (in guaraníes per year 2006-2022)

Source: Article 5 of the General Budget of the Nation for each year.

In 2021, private companies imported 2,361 liters of fuels. If these companies have exactly the same operating cost as Petropar, except for the government contribution, the private companies earned an extra Gs. 243.4 per liter, or about Gs. 574,865 million (USD 83 million). It is a round business to follow Petropar’s price if Petropar has higher costs.

How can this mistake be corrected and what would be the consequences? An alternative to the intergovernmental contribution is to distribute the contribution in the Selective Excise Tax (ISC in spanish) on fuels. Since the ISC applies to all companies, the Gs. 110,000,000,000,000 are divided into 2,813 million liters (the 452 of Petropar plus the 2,361 of the private companies), which yields Gs. 39 per liter. Therefore, the government could increase the ISC on fuels by Gs. 39 and eliminate Petropar’s intergovernmental contribution, keeping the total collected by the Treasury as a fixed rate. Since Petropar gets a cost of Gs. 243.4 per liter and increases Gs. 39 in ISC, it has a net saving of Gs. 204.4 per liter (calculations made with data from 2021).

In conclusion, the high number of gas stations could be linked to Petropar’s inefficient cost structure. Part of this inefficiency lies in the “intergovernmental contribution”, which can (and we believe should) be transferred to the ISC for all fuel companies. With this change of intergovernmental contribution for an increase in the ISC, the government keeps its collection fixed and reduces the cost for Petropar, which would allow it to reduce its prices. The private companies will stop taking that extraordinary profit without much competition among themselves (which today leads them to open a gas station on every corner), which, therefore, will stimulate a move away from the logic of oligopoly and towards a situation of internal competition. This change could be made by the government and the congress in a few days.

Cover image: ABC Color