By Rodrigo Ibarrola

In the last few weeks, fuel prices have undergone variations, first downward, then upward, and finally downward again due to Petropar’s position of maintaining its prices. These movements were justified by the rise in the dollar exchange rate. Of course, news such as these possible increases cause a lot of irritation among consumers. The government, for its part, is taking a more passive position or is letting events take their course, i.e., it does not plan to do anything about it.

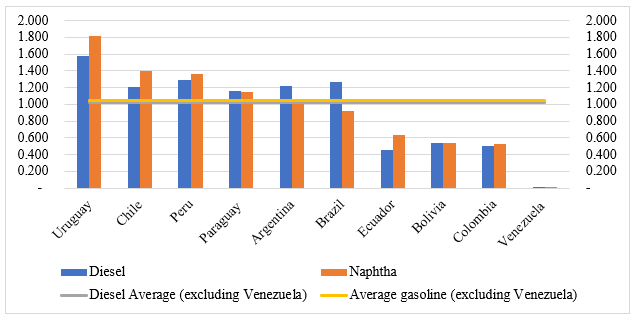

And we say “do nothing” because there is no way that, in this context of inflation due to external shocks (Ukraine war, insufficient refining capacity, freight bottleneck, etc.), the price of fuel can drop without state intervention. It is true that Paraguay has prices above the average for the region (Graph 1), but it is also true that the other countries intervene in one way or another in the market to mitigate the inflationary effect. There is practically no country that does not do so.

Figure 1. Average fuel prices in South American countries, in dollars

Source: Own, with data from Global Petrol Price, as of 10/17/22. Note: the price in Argentina is lower for Paraguayans if purchased with pesos acquired in our territory.

Before reviewing the regional measures, it is necessary to clarify that Paraguay does not import crude oil because it does not have refineries. What is acquired from abroad are derivatives, i.e. diesel or naphtha. The prices of these, in recent months, have remained stable, although relatively high, after an upward trend.

Contrary to what some experts say, the price of oil is not transferred instantaneously to the cost of fuel. The latter operates with a certain lag since it first needs to be refined to obtain the derivatives, so neither the rise nor the fall in prices should have a rapid impact on the international price of fuels. But this is also where importers’ expectations regarding future replacement costs come into play. This, in turn, causes cost variations to be passed on to consumers, which in practice generates what is called “asymmetry in price transmission”, which is basically when prices do not respond in the same way to a rise or fall in the international price, either in speed or magnitude. Thus, in the face of an expected rise, companies generally adjust their margins in anticipation of a higher future cost. But that is another story. What is certain is that sooner or later the rise in oil prices will have to have an impact on the final price, and it is in situations like the current ones that governments intervene to soften the abrupt changes.

All countries use some mechanism to mitigate fuel price increases, including explicit subsidies, stabilization funds, tax cuts, price controls through state-owned companies, or a combination of these. Thus, we will present a summary of the interventions in the region.

First, we will address explicit subsidies. This measure is taken by countries such as Bolivia, which is a producer and, in addition, aggressively subsidizes fuels by up to 80%, thus achieving one of the lowest fuel prices in the region. In Ecuador, another of the countries with the cheapest fuels in the region, the price increases provoked protests in that country, so the government decided to lower prices by decree and subsidize them. Subsidies cover 59% of the cost of diesel oil and between 37% and 45% of the price of gasoline. However, these measures have high costs; in Bolivia, the subsidy is expected to reach US$ 1 billion and in Ecuador, around US$ 2,988 million.

It goes without saying that fuels in Venezuela have been highly subsidized for many years now, and it competes with Libya and Iran as to who has the cheapest fuel in the world.

Next are the countries that chose to reduce taxes. Our Brazilian neighbors enacted a law to lower the maximum threshold of the tax on the circulation of goods and transportation services (ICMS) to a ceiling of 18% in the different states, and also reduced federal taxes to zero, which is particularly sensitive, as federal taxes fund social security. Mexico, another oil producer, has decided to exempt 100% of the Special Tax on Fuels at peak times (March to August), which they call a fiscal stimulus. Currently, this stimulus is maintained at 100% for diesel, and between 76% and 94% for naphtha. This measure is especially effective when tax rates are high.

Then there are the countries that use a stabilization fund. Chile has had a fund called the Fuel Price Stabilization Mechanism (MEPCO) since 2014, whose purpose is to maintain the price of fuels within a range, which works by adjusting the Specific Fuel Tax, according to need. When prices are low, the tax rate feeds the fund; when they are high, the price is subsidized with what was previously collected. Peru, for its part, has a mechanism called the Fuel Price Stabilization Fund (FEPC) with rules like the Chilean fund, as does Colombia. The cost of these policies would reach some US$ 3 billion for Chile, US$ 8486 million for Colombia and US$ 803 million for Peru.

What about Argentina? Contrary to popular belief, there is no specific fuel subsidy in Argentina. However, as an oil-producing country and thanks to its control of Yacimientos Petrolíferos Federales (YPF), it sells crude oil at low prices, which puts downward pressure on the prices of refined products. Companies that cannot obtain crude oil from YPF are forced to give up margins, lowering the price, or lose market share. It also establishes caps on fuel prices, thus ensuring that price variation does not keep pace with general inflation. Uruguay has forced the National Fuel, Alcohol and Portland Administration (ANCAP), which holds the import monopoly and regulates the market, to sell fuels below cost. In this way it has managed to avoid a further jump in the price, which is already the highest in the region. The cost for Uruguay, until May 2022, is a deficit for the company of US$148 million (consider that the total for 2021 was US$159 million).

Contrary to what some experts say, the price of oil is not transferred instantaneously to the cost of fuel. The latter operates with a certain lag since it first needs to be refined to obtain the derivatives, so neither the rise nor the fall in prices should have a rapid impact on the international price of fuels.

Finally, Paraguay, as we know, reduced the tax base for the determination of the Selective Consumption Tax (ISC) on fuels and achieved a minimum incidence of taxes on the price of fuels. In addition, it implemented a fuel subsidy scheme for three weeks, which it had to give in due to pressure from the business associations. This scheme, which subsidized diesel type 3 and 93 octane naphtha, cost 8.9 million dollars and lasted about 17 days.

In general, all governments have taken measures to mitigate fuel price increases depending on their fiscal space and financing capacity. Paraguay, with narrow margins in both, has not intervened like other countries. The governments’ decision is since these prices affect not only individual consumers, but also industries, businesses and a large part of their value chain, making intervention imperative to avoid worse consequences and, of course, social upheavals.

Cover image: Última Hora