Rodrigo Ibarrola

According to its third meaning, “tradition” is -according to the RAE- the doctrine, custom preserved in a people by transmission from parents to children or, if we refer to religions -fourth meaning-, each of the teachings or doctrines transmitted orally or in writing since ancient times. Therefore, the traditional family would be that which models Paraguayan homes according to the ideas, norms, or customs of the past. In this disquisition, two questions immediately arise: first, what is the structure of the traditional family and, second, when does this tradition begin?

If we go back to our Guarani ancestors, we find that the family, although patrilineal, was often matrilocal, that is, the male moved into the woman’s house. They were, for the most part, monogamous, although the chiefs had the privilege of polygamy, even though this did not create a difference between the kuña and the tembireko (among the Guayakí, polyandry was frequent). The union consisted of a simple public act in which the couple left for the forest and on their return, they were married or declared themselves married when they decided to settle together in the same house. Although rare with children in between, the “divorce” consisted of a simple separation where each one takes his own: the work utensils, such as the shovel, the hook and the arrows remain with the man, the kitchen utensils with the woman. Marriage or matrimonial union was not a defined institution.

The families, in turn, lived in communal houses where several other families were housed in kinship ties. This extended family structure had its socioeconomic function: more hands for farming, and defense against possible wars. This extended unit, which could be composed of more than a hundred people, also had the purpose of helping each other in difficult times, and the raising of the offspring fell within the communal responsibility. There was no real sense of ownership, neither of human relations nor of property. The institution of parental authority was unknown to them. Although intersexual differences in tasks were present, they were not based on relations of domination, nor was there any other form of exploitation. Relations of domination and subordination would come later, with the Spaniards.

The missionaries who accompanied the newly arrived Europeans did not accept the Guarani concept of union, so they imposed monogamy, the nuclear family model and prohibited divorce. However, the traditional image of the European woman and family was unrealistic, even among the aristocracy of the time. The encomendero lived surrounded by women: the legitimate wife or not and generally a series of concubines –yanaconas or maidservants- plus the children they bore him, relatives and male yanaconas. The morality promoted by the religious was difficult for the indigenous people to understand, since it was not complied with even by the prelates themselves. Occasional relationships and concubinage became the rule and most mestizos were born out of wedlock. The relationships established in this period would mark the sexual habits of the urban families, which used the women of the domestic service as sexual initiator of the son or as an object of pleasure for the boss.

Dr. Francia’s decree, which restricted the marriage of foreigners with white criollas, only increased consensual unions. Thus, concubinage, pregnancy and out-of-wedlock births carried no stigma even in the highest strata of society. Although the elite, which became socially active during the time of Don Carlos A. López, respected Catholic morality to a greater extent, it was too small to influence the general population. López was not even successful with his sons, Benigno and Francisco. This is reflected, for example, in the data collected by Barbara Potthast in 1846 which indicates that there were only 16 marriages in the parish of La Encarnación (capital), with a population of 9668 people. In addition, historian Ana Barreto indicates that approximately half of Paraguayan households were headed by a couple – either married or not – while the other half had only one person, usually a woman, as head of household. However, most of them were not widowed, but single. On the other hand, the Statistical Yearbook of 1886 recorded 115 marriages in a population of 263 thousand inhabitants for the whole country, about 0.4 marriages per 1000 inhabitants (a value that in 2021 is at 2.68). There is a disconnection between marriage and family, and the latter does not need the former to subsist.

Military service and the conditions of yerba mate production caused long absences of men from home (with uncertain return), so the institution of marriage limited the action of women in their civilian life by preventing them from engaging in commerce, filing lawsuits, or disposing of their property. Basically, it was a bond. Given the uncertainty, women often established another relationship or left for the city in search of work in the homes of other families to do washing, ironing, or caring for the employer’s children, or as live-in maid The slavery of the mensú in the yerba fields would continue until the middle of the 20th century. Thus, returning to our days, we find that the reality has not changed much, only 37% of the heads of household are made up of a married couple in the third quarter of 2022, according to the Permanent Household Survey.

The traditional marriage that was for five thousand years the primary means of transferring property, occupational status, personal contacts, money, tools, livestock and women between generations and kinship groups was finally overthrown. But it was not gays or lesbians who did it, but heterosexuals themselves who brought about this revolution.

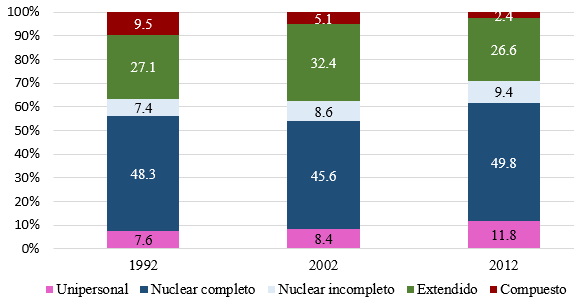

Our Constitution, although it speaks of family, does not offer what should be understood by it. Nevertheless, the collective imagination still maintains the nuclear family model of father, mother, and children, united in a religious ceremony -even better if it is Catholic- as the ideal. However, it is not that today the reality is different, but rather that it has been the rule for decades, but not always accepted. In Graph 1, it can be clearly seen that the proportion of nuclear families (couple and children) in the population has remained relatively constant over the last 30 years, reaching a little less than half of all families. The proportion of families in which only one parent is present (incomplete nuclear) and people living alone (unipersonal) has increased slightly, while the number of extended families (nuclear plus other relatives) and compound families (nuclear or extended plus other people not related to the head of the family) has decreased.

Distribution of households by type

Source: STP/DGEEC. National Population and Housing Census. Years 1992, 2002 and 2012.

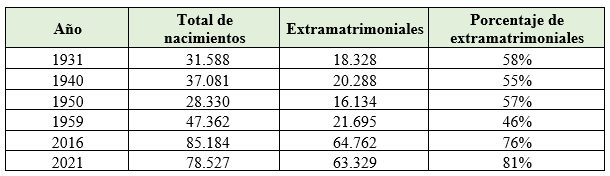

In practice, marriage is not what is idealized. Married people divorce and many children are born out of wedlock. The law has had to adapt to the new forms (de facto unions). One index that reflects this is the proportion of children registered as born out of wedlock, which is shown in Table 1, showing the increase over time.

Table 1. Live births registered by filiation

Source: Velázquez Seiferheld, D. (2022). The family in Paraguay: historical fragments (Part I). El Nacional; STP/DGEEC. (2016). Vital Statistics; INE. (2021).

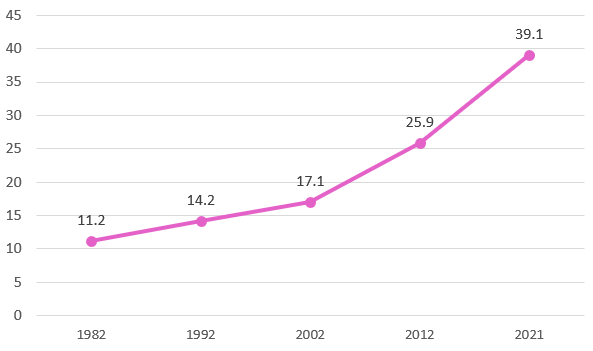

Divorce and unwed parenthood were common in many societies in the past, but almost never coexisted with women’s right to initiate divorce, or the ability of so many single women to support themselves and their children (see Figure 2). As women gained more legal rights and greater job opportunities, the influence of the marriage culture weakened. Young people began to delay marriage. Premarital sex and cohabitation lost their stigma.

Figure 2. Evolution of the female household headship rate

Source: STP/DGEEC. National Population and Housing Census, 1982, 1992, 2002 and 2012 and Permanent Household Survey 2021.

There is a growing proportion of married people today who will never have children, not because of infertility, but by choice. This is a big change from the past, when childlessness was an economic disaster and often led to divorce, even when the couple would have preferred to stay together.

The traditional marriage that was for five thousand years the primary means of transferring property, occupational status, personal contacts, money, tools, livestock and women between generations and kinship groups was finally overthrown. But it was not gays or lesbians who did it, but heterosexuals themselves who brought about this revolution.

The series of interrelated political, economic, and cultural changes in the 17th century began to erode the ancient functions of marriage and challenged the right of parents, local elites and government to limit individual autonomy in personal life, including marriage. The revolutionary new ideal of love marriage was born, changing thousands of years of history. Suddenly, couples were to invest more of their emotional energy in each other and their children than in their natal families, their relatives, their friends, and their sponsors.

Those same values that we now consider traditional, which invest marriage with great emotional weight in people’s lives, have an inherent tendency to undermine the stability of marriage as an institution.

Finally, the demand by gays and lesbians for legal recognition of their unions is a symptom, not the cause, of how much and how irreversibly marriage has changed.

Cover image: Crónica.