By Lorena Soler.*

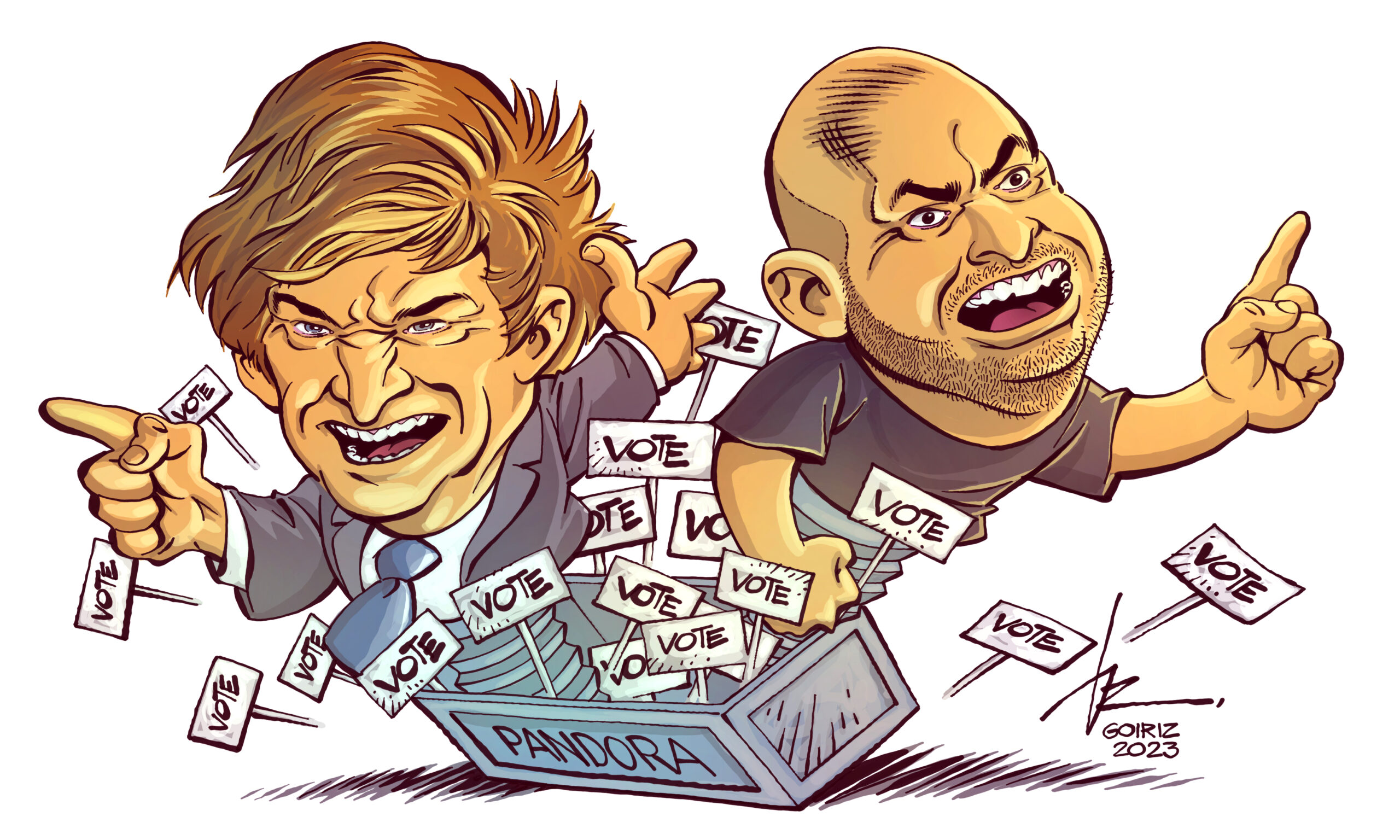

Argentina and Paraguay share a long common history. In addition to the War of the Triple Alliance, the death of Sarmiento, the exile and return of Perón, the return of war trophies, political exiles and culinary transnationalization, they have recently shared two businessmen presidents (Mauricio Macri and Horacio Cartes) as part of the repertoire offered by the new right wing. In the current situation, within this same repertoire, two extra-partisan candidates for president, Javier Milei and Payo Cubas, appear in the electoral scenario of 2023, with some singularities that I would like to highlight.

In the first place, both are the cause and not the consequence of a political system that has little to offer and of a world disorder that provides diffuse liberal or democratic models to emulate. They are part of what Steven Levitsky and Daniel Ziblatt have called the death of democracy and which Marcos Pérez Talía has already reviewed in this same space. In this scenario, then, how are the current congressman Javier Milei of Argentina and the former senator Payo Cubas of Paraguay similar, and how are they different?

Both political candidates present themselves with speeches centered on the denunciation of the political class or “caste”. To fight against it, they seek to reduce it to its minimum expression, even at the cost of closing basic institutions of representative democracies and reducing state bureaucracy. In the perspective of both, being part of these institutions overcomes a double moral problem: on the one hand, it implies being part of a corrupt apparatus that infects the subjects; on the other hand, there is an economic cost of this parasitic system that is accompanied by privileges that are financed with the “hunger of the people”. While Milei points out that “political parasites hide behind the poor”, Payo Cubas proposes the death penalty for the corrupt.

Milei and Cubas present a dichotomy between the common man vs. the political man (as if we all were not), concentrating the problems of social dysfunctionality in the institutions of the republic or of the democratic regime. If necessary, they propose the closure of Congress and the concentration of decisions in the Executive Power, without ruling out the use of security forces.

both show that it is possible to do and transform a reality that, at times, seems to be designed by the coaching of the focus groups. All scripted. In the face of this, both Payo and Milei present formulas, which may sound magical, but what is politics if not the possibility of offering illusions? It could be said that, finally, political realism has eaten the campaign. And the alternative is phallic.

Both also present themselves as outsiders, although they are part of the class they come to denounce. Payo is a long-time politician: Member of the house of representatives (1993-1998), candidate for Governor of Alto Paraná (1998) and candidate for Mayor of Ciudad del Este (2001). He was elected Senator in 2018. But, for the narrative in which he is inserted, he has in his favor having been expelled from the Upper House (2019). That plus of legitimacy allows him to say: I was there but I am not like “them”, so much so that I should have been expelled. Milei, is an economist in the financial sector and in his political career he was a journalist for newspapers and radios, recently an actor and since 2019 he created his own party. In 2021 he was a candidate for member of the house for the City of Buenos Aires and became the third force in the district, after “Juntos por el Cambio” and “Frente de Todos.”

It is striking that in no case are the problems they observe as dysfunctional attributable to the economic elites (the businessmen or landowners or any other dominant economic subject), leaving the “guilt” to the political class and the state bureaucracy. Perhaps, therein lies the idea of meritocracy: that man in the private world harvests, unlike man in the public sphere, the personal efforts of his fortune. However, here Payo Cubas differs from Javier Milei by presenting a range of measures aimed at generating a more egalitarian social order.

Cubas proposes a nationalist discourse against the so-called brasiguayos (referring to Paraguayans of Brazilian origin who appropriate land and engage in intensive agriculture), proposes to create taxes on income from agricultural activities and a tax on the export of commodities. He also claims to be heir to the colorado tradition as a “romantic anarchist, republican and nationalist”.

In contrast, much less heterodox, Milei is a candidate more concerned about being accepted by the world of the economic establishment -from where he comes from- and seeks the altar in old-fashioned prescriptions of a neoliberalism in disuse. Dollarization of the economy, closing of the Central Bank and elimination of all taxes that “are theft”.

The counterpoints also go to the styles and scope of their campaigns. Payo Cubas does not show a great investment of money, and social networks have played in his favor. He has a record number of followers on TikTok and this shows his capacity to appeal to certain social and age sectors. He does not have, like Milei, national chains in related media. He does not wear fashionable suits, does not have advisors or hairdressers, and does not live in the richest area of the city. Nor does he finance his campaigns and increase his personal fortune with invitations in dollars or as an influencer. Payo Cubas, son of a military man, always dresses in austere black, and flips burgers in the street to finance his campaign. He is his own manager with a cell phone in his hand, from live to live, he takes pictures with ordinary citizens and knows by heart the prices of each cut of meat. The name of each of his movements exhibits this difference which, at the same time, serves as a slogan for these breakaway politicians: “La Libertad Avanza” (Freedom Advances) is the name of Milei’s platform, while the Cubas movement was named “Cruzada Nacional” (National Crusade).

From the news channel “La Nación Mas”, Milei speaks to the Argentine elite and participates in the bunkers of businessmen whom he tries to convince, while he prepares shows in black cloaks for young people to whom he offers freedom. Very different is Payo Cubas, who does not seek that electorate. He knew how to create the figure of a politician who openly confronts a rotten system, whose only available means to fight is to “come forward” -painting graffiti on the prosecutor’s office and houses of politicians suspected of corruption, defecating in the judge’s office, among other direct actions-. Thus, Payo’s statement “the belt will be the symbol of the revolution”, became the magnificent phrase for a jaded electorate.

However, beyond their reps, it is very likely that both candidates will reap their votes from the same social sectors, those which, in effect, the party candidates have not been able to appeal to. Cubas and Milei will end up gathering the will of a social sector of citizens who see how their incomes and welfare are degrading, and who increasingly distrust the ways in which the classic public and representative institutions that fail to fulfill their functions operate.

Both candidates are, in some sense, the result of the loss of a common horizon, of a collective possible, of broken basic consensuses and of certain responses that liberal democracies failed to make. They are political activists who know how to read this uneasiness and transfigure it into electoral capacities with uncertain results. Because the right, as Pablo Stefanoni has already said, presents itself with “rebellious models” while the left, and its derivations, watches in astonishment the dismantling of the last remnants of a State that used to present some welfare ambitions.

Payo and Milei, aspire to govern and they present very attractive mottos, in front of the impotence of other candidates and of the officialism that usually argue at length the “why they have not been able to”. In both exponents, the structural conditionings are suspended, whether they be of the pandemic, of the foreign debt, of the unions or of the social movements. Before the impossibility, before the Homus Resignatus that floods our common sense, as Lucas Rubinich says, both show that it is possible to do and transform a reality that, at times, seems to be designed by the coaching of the focus groups. All scripted. In the face of this, both Payo and Milei present formulas, which may sound magical, but what is politics if not the possibility of offering illusions? It could be said that, finally, political realism has eaten the campaign. And the alternative is phallic.

* Professor and researcher at CONICET, UBA and IEALC.

Cover image: Roberto Goiriz