By Ivonne Aristizabal.*

According to data from the National Statistics Institute (INE), 37.2% of households are headed by a woman. Of these, 60% work in the communal, social, and personal services sector, as well as in commerce, restaurants, and self-employment. One of the main barriers faced by women in the labor market is informality, with much higher rates than men. This situation is transferred to prisons in our country, where most women are heads of household. This article seeks to make visible the working conditions of women serving prison sentences in Buen Pastor, the main women’s penitentiary nationwide. The situation is serious and must be urgently addressed in Paraguay.

According to the Inter-American Court of Human Rights, “when a woman is deprived of her liberty, her entire family is deprived“. This phrase exposes deep and structural inequalities: when a man is deprived of his liberty, it is the woman who is responsible for supporting the household and caring for the children. Conversely, however, when women are locked up, the children tend to grow up in the same context of confinement or in the care of family. In both cases, it is the mothers who try to support their households, even when they are deprived of their liberty.

For the preparation of the article, data from the annual survey of “Corazón Libre”, a social project that supports the rehabilitation and social reintegration of women deprived of liberty at Buen Pastor and the education of their children, were accessed.

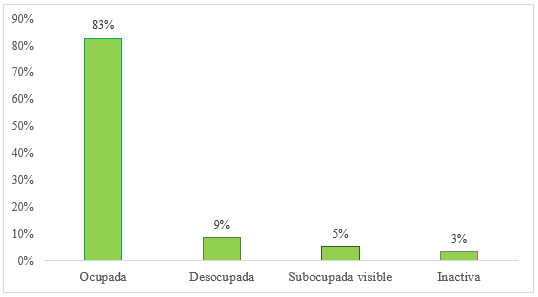

The total population of the penitentiary is 436 people (November 2022 data). According to the survey, 57% of the women in the sample stated that they were heads of household. Regarding their occupation before confinement, 83% had an occupation (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Occupation of women before confinement

Source: Corazón Libre Survey, year 2022.

Source: Corazón Libre Survey, year 2022.

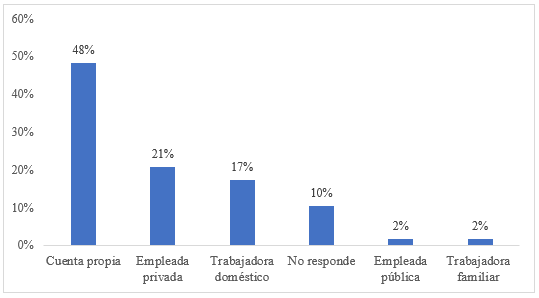

Regarding the occupational categories of the women before confinement, 48% were self-employed, 21% were employed in a private business, while 17% did housework (Figure 2). It is worth mentioning that 10% did not respond to the consultation.

Figure 2: Women’s occupational category before confinement

Source: Corazón Libre Survey, year 2022.

Source: Corazón Libre Survey, year 2022.

The situation of these occupations shows the drama of formalization. The vast majority supported their households in informal conditions. Seventy-two percent stated that they had not contributed to a pension fund, while 95% stated that they did not have a RUC (Tax ID). Notoriously, precarious, and informal jobs limit financial inclusion. Seventy-nine percent of the women indicated that they had never used a bank account and only half (50%) used electronic wallets.

It is of utmost urgency to generate policies that focus on the type of population that is currently deprived of their liberty. The promotion and generation of work in decent conditions not only contributes to the reinsertion of women but is also fundamental for them to continue supporting their households when they are left without their main breadwinner.

It is known that the lack of inclusion in the financial system limits economic autonomy, generating greater inequality with respect to men. Through education and inclusion, women’s economic empowerment and access to formal products with lower costs than informal ones can be achieved, in direct relation to their economic situation.

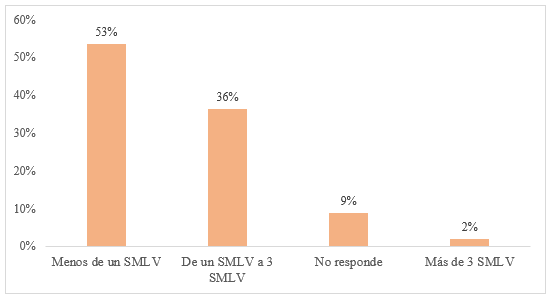

In relation to income, the majority indicated that they earned less than the current legal minimum wage (SMLV) (Figure 3). During confinement, the highest percentage of these women kept their income below the minimum wage. What is striking is that, even under these conditions, 21% of the total number of women heads of household send money to their families, thus maintaining their households from the penitentiary through jobs such as cleaning, cooking, hairdressing, and cardboard work.

Graph 3: Women’s income before confinement according to Legal Minimum Wage in Force (SMLV)

Note 1: The current minimum wage is Gs. 2,550,307. Source: Corazón Libre Survey, year 2022.

Note 1: The current minimum wage is Gs. 2,550,307. Source: Corazón Libre Survey, year 2022.

The situation of the women carries over to that of the children, who can live with their mothers at Buen Pastor until they are four years old. But it is the mothers who must cover food, hygiene and clothing expenses. Therefore, for these women and their families, the income they generate inside the prison is of vital importance. Whether they are released or not, there is one reality that remains unchanged, and that is that they continue to be the breadwinners of their families.

Considering the situation of women heads of household in confinement, the next government under the recently elected president, Santiago Peña, should propose solutions to the crisis of the prison system with a strong gender perspective. The fact that women heads of household are imprisoned constitutes a social and economic problem that goes beyond the prison perimeter. Without an approach that makes this situation visible, the problem would not even be identifiable.

As a first step, policies are needed to benefit women deprived of their liberty from an approach that considers their families, considering their composition, the employment situation of their members, the way in which care is organized and their socioeconomic status.

These policies should be based on the Bangkok Rules established by the United Nations in 2010. It is the most comprehensive document on the rights of women deprived of liberty currently in existence, which also showcases the situation of the children of these women. It sets out a series of principles that policies should consider, such as gender-sensitive training for prison staff and care for nursing mothers, giving priority to girls and boys.

Individualizing and identifying the conditions of these women, such as nursing mothers or those who have their children in children’s homes inside prisons, will also be essential to produce public policies aimed at this population from a gender and basic elementary rights perspective.

In Paraguay’s prison system there is a significant level of overcrowding and other conditions that can limit people’s social reintegration. This is worse in the case of women, especially those who are the economic heads of households. It is of utmost urgency to generate policies that focus on the type of population that is currently deprived of their liberty. The promotion and generation of work in decent conditions not only contributes to the reinsertion of women but is also fundamental for them to continue supporting their households when they are left without their main breadwinner.

* Economist and Research Coordinator of the “Corazón Libre” project.

Cover image: Yuki Yshizuka