By Dahiana Ayala.*

The current crisis in the labor market seems to be taking on serious dimensions, especially for women. The labor precariousness that affects women on the verge of poverty, even extreme poverty, is expressed in part-time, fragmented and poorly paid jobs. The new government of Santiago Peña will have to find an effective solution to the terrible working conditions that the market offers women. Perhaps the answer lies in empowering women in the design of economic and social recovery plans from a feminist perspective.

Paraguayan women workers converge in a labor market that offers them very low-skilled, part-time jobs without contracts. This type of informal work, with its inherent flexibility, exists outside the provisions of the law.

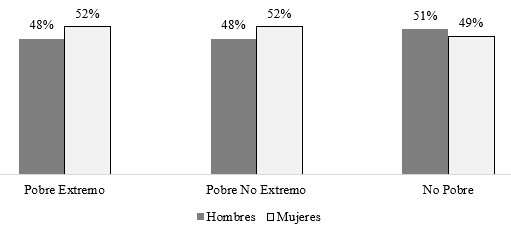

Since 2019, the government has been regulating part-time employment, which does not mean that the precariousness of female labor has ended. Women are always the first to be affected by the destructuring of the labor market. The pattern that repeats itself is one where women’s work is priced low, and which during economic crises is exacerbated. As a result, the impoverishment of women is increasing and worse than the situation of men. By 2022, the poverty rate of women has been higher than that of men: 731 thousand women are poor while men account for a total of 671 thousand. And if we focus on extreme poverty, there are 216 thousand poor women compared to 198 thousand men in the same situation. In percentage terms, the division of poverty by gender can be seen in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Poverty and Gender (%)

Source: Own, based on data from the Household Survey, INE-2022.

Source: Own, based on data from the Household Survey, INE-2022.

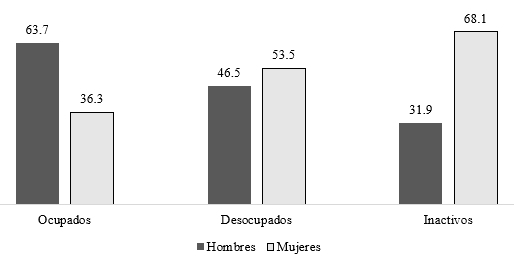

When we delve deeper into the analysis of inequalities in the labor market, the data show that the situation of women worsens if they are poor. Figure 2 reveals that, of the total number of employed people living in poverty, 63.7% are men and 36.3% are women. In terms of total unemployment, the situation is reversed, affecting 53.5% of women and 46.5% of men. And if we analyze inactivity, the figures are very significant: of the total number of inactive people living in poverty, 68.1% are women and 31.9% are men. This reflects the fact that female poverty especially conditions women to the worst jobs, the worst salaries, and the worst working conditions.

Figure 2: Poverty, Activity and Gender (%)

Source: Own, based on data from the Household Survey, INE-2022.

Source: Own, based on data from the Household Survey, INE-2022.

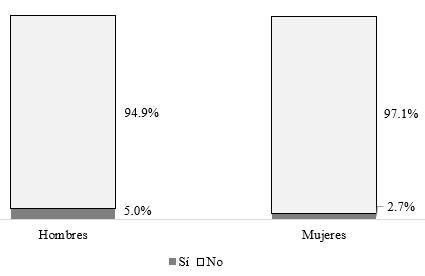

When we look at the pension contribution of employed people living in poverty (Figure 3), men reach 5% and women 2.7%. Although both are vulnerable because they are not protected by social security, in the long run it ends up being even more detrimental for women since the system never implements labor protection policies for the types of jobs that women mostly have access to: part-time, domestic, and low-income jobs.

Figure 3: Pension Contribution, Gender and Poverty (%)

Source: Own, based on data from the Household Survey, INE-2022.

Source: Own, based on data from the Household Survey, INE-2022.

Unfortunately, women are pushed into informal employment. In the absence of comprehensive care policies and the unfair distribution of tasks within households, they are more likely to accept undignified working conditions because “flexible” schedules allow them to reconcile work and domestic life.

In the case of women raising children alone, the obstacles to their participation in the labor market are not only monetary. They lie in the low professionalization and quality of certain jobs in which women are overrepresented, such as cleaning services and personal and health care. This is because the skills required to perform these tasks – caring, educating, cleaning, assisting – are devalued in the market because they are considered innate or natural to women. Another immense barrier to accessing the labor market has to do with the insufficiency of services such as day care centers and full-time schools, which would allow women to have their own time to get a job and develop professionally. These conditions continue to deepen female impoverishment and, above all, women’s lack of autonomy.

Paraguayan women workers converge in a labor market that offers them very low-skilled, part-time jobs without contracts. This type of informal work, with its inherent flexibility, exists outside the provisions of the law.

In view of the enormous difficulties faced by women in the labor market, one of the commitments to be assumed by the new Colorado government, headed by Santiago Peña, is to effectively integrate the gender dimension in the development and implementation of public policies for the fight against poverty and labor precariousness. The new president and his entire cabinet, particularly some ministries such as Labor, Employment and Social Security, Social Development and Women’s Affairs, must be clear that solutions cannot be generated if women are not considered in decision making.

Rethinking alternatives for women in the labor market must start from a thorough knowledge of the existing gender inequalities, which are even more pronounced in the case of poor women, rural women, indigenous women, women of African descent, trans women, women deprived of their freedom, women raising children alone and caring for other family members, women employed in service industries, women with disabilities, women victims of violence, among others.

Public policies designed in this sense must have the capacity to correct the disparity between men and women. This can be achieved by making the awarding of public contracts conditional on respect for wage equality between men and women, and by generating mechanisms to increase the value of salaries in essential professions where women represent the greatest number, occupations such as the care of dependents (babies, children, and the elderly).

Plans must have a comprehensive gender vision and must be transversal to all areas of women’s lives. For example, the French government, as part of its policy of equality between men and women for the years 2023-2027, has implemented a couple of actions based on 5 fundamental pillars: the fight against gender violence, economic opportunities for women, comprehensive education for girls, health, and political emancipation.

Each of these pillars is reinforced through specific actions. In the case of the pillar linked to economic opportunities, it emphasizes the role of companies and the civil service in achieving equal pay and access to positions of responsibility through a professional equality index to which companies will be subject. It also provides financial support for young women to access digital and technological professions.

To promote policies of this type, the government will require, in addition to a great deal of expertise, a strong commitment to reducing gender-based inequalities. To do so, it will be essential to recognize them as such, without euphemisms.

* Doctoral candidate in Economics and Sociology of Work at Aix Marseille Université

Cover image: Yuki Yshizuka for Terere Cómplice