*Por Jorge Rolo´n Luna

Several countries experience profound effects on their economies, social dynamics, and institutional frameworks due to the complexities of drug trafficking. Paraguay, burdened by this nefarious trade, is often dubbed a “narco-state.” As I have previously highlighted, the primary factors that categorize a state as a “narcostate” are:

a) the states’ active engagement in drug trafficking, b) the substantial economic influence of drug trafficking, and c) vast areas dedicated to illegal farming.

In this article, I want to address what is often perceived as the crux of the matter: the responsibility and implication of state agents in the illicit trade. Firstly, it’s undeniable that drug trafficking in Paraguay was established and thrived under a state and party (the A.N.R.) protection scheme. This happened from its early days with marijuana cultivation to its consolidation as a transit and re-export country for cocaine, including heroin trafficking in the 1970s. High-ranking military officers and border politicians were part of this scheme, and today, the typology of officials has diversified and expanded.

The case of former President Gen. Andrés Rodríguez (1989-1993) is emblematic. He was directly involved in heroin trafficking in the 1970s and later in cocaine trafficking, according to numerous sources, including declassified American documents. Another powerful example from party politics is the Morel Clan, active leaders of the Colorado section of Capitán Bado. They are often considered the founders of marijuana trafficking to Brazil (father and sons brutally murdered in 2001). This model solidified in subsequent decades, with no checks or corrections applied, leading many to believe that Paraguay had become a narco-state.

The results of the recent elections have brought the Cartismo faction to the presidency, overwhelmingly pointed out for its ties to all kinds of illicit businesses, which does not bode well. This will likely result in strong pressures on the Public Ministry to hinder or slow down the modest advances against political impunity. The coming months and years will be crucial in determining the model that will emerge from these back-and-forths between politics and drug trafficking.

Several former presidents, high-ranking military officers, deputies, senators, governors, mayors, and municipal councilors (especially from border areas) have historically been involved in the business. Protected by a weak, dependent, and corrupt judicial system, by the police (where there are also enthusiastic traffickers), and by the anti-drug agency (SENAD). Such a lucrative business model, in a structurally corrupt country with a primitive economy, few opportunities, and incentives for advanced capitalist growth, created the perfect conditions. Obviously, such a lucrative industry could not have remained outside the interest of the hegemonic party, much of the political class, and the civil and repressive bureaucracy (Armed Forces, police, and anti-drugs).

It can be said that the business was born from the basic leadership of the Colorado party in the border area, with the approval and protection of the power elite (military and civil). This is quite logical: during the Stroessner dictatorship, it was unthinkable to be an opponent and a drug trafficker at the same time. Today, as the country is integrated into the global drug market, the money it generates is one of the pillars of the Colorado officialdom, financing its campaigns. In addition, it generates a multimillion-dollar spillover to business sectors (exchange houses, the financial system, especially) and much of the societies in its area of influence and throughout the country. Today, the business diversifies and expands with dimensions far removed from its modest beginnings in the fields of Amambay.

The theoretical problem with subscribing to the narco-state thesis is that it implies understanding these state agents as the State itself and maintaining that they have acted and acted on its behalf to promote drug trafficking. However, one should not confuse the fact that there are officials who dare to participate in this illegal trade with the State as a whole engaging in it. If we also accepted that simplistic definition from certain constitutional law manuals that say: “the State is all of us,” in a narco-state, we would all be drug traffickers. Simply conceiving of the State as a set of social relations prevents concluding, no matter how widespread the rot, that the Paraguayan State as a whole is dedicated to drug trafficking. The State is also a set of diverse institutions, with histories, ethos, and different institutional missions, something not understood by those who visualize it as a homogeneous block with a single political will.

Thus, it’s crucial to differentiate between a state where drug traffickers operate and one where the entire state apparatus controls, promotes and oversees drug trafficking. Available evidence suggests that segments of Paraguay’s political elite and public sector have had, and continue to have, ties to drug trafficking. Some individuals fully embody the role of drug traffickers. This is particularly evident in border towns, where local councilors and mayors have directly engaged in the trade, though the exact extent remains hard to quantify. The menace of targeted assassinations has also affected them, not necessarily because they opposed drug trafficking.

A significant point to note is that, over the years, the Paraguayan State has selectively targeted alleged and confirmed drug traffickers. Many of them have been prosecuted, incarcerated, or extradited to other countries. However, there are glaring exceptions, such as Fahd Yamil Georges and the late Jorge Raafat, who appeared to be seemingly untouched by our police, anti-drug agencies, and judicial system. In Georges’ case, he was never held accountable for the murder of journalist Santiago Leguizamón, only facing consequences under Brazilian law.

However, other prominent political figures implicated in drug trafficking, money laundering, and related offenses have faced a different outcome. The prevailing trend has been one of absolute impunity. A prime example is the former President Andrés Rodríguez. He wasn’t the only leader to ascend to the highest office while bearing grave allegations of drug trafficking connections. This pattern of shielding high-ranking politicians from accountability, especially when juxtaposed with the fate of many major drug traffickers, suggests that political power remains dominant over “narco” influence.

Today, the prevailing model -particularly in its most comprehensive form- appears to be temporarily waning. This is evident from the cases involving former Colorado party deputies Ulises Quintana and Juan Carlos Osorio, as well as Operation A Ultranza, which now implicates Senator Erico Galeano, also from the Colorado party, who is currently under scrutiny by the prosecution. The recent elections have elevated the Cartismo faction to the presidency, a group widely criticized for its connections to various illicit activities. This ascendancy is concerning and may lead to increased pressures on the Public Ministry, potentially stalling or slowing the modest progress made in the combat against political impunity. The dynamics between politics and drug trafficking in the upcoming months and years will be pivotal in shaping the future drug trafficking landscape.

While the association of prominent public figures with drug trafficking is undeniable, it doesn’t implicate the entire state apparatus. It’s evident that the proceeds from drug trafficking are generously distributed and welcomed across broad segments of the establishment, including certain opposition groups, bureaucratic circles, the business community, and the general populace. While the state as a whole isn’t engaged in drug trafficking, it undeniably operates within a drug-trafficking environment.

*Researcher. Former director of the Observatory of Coexistence and Citizen Security of the Ministry of the Interior.

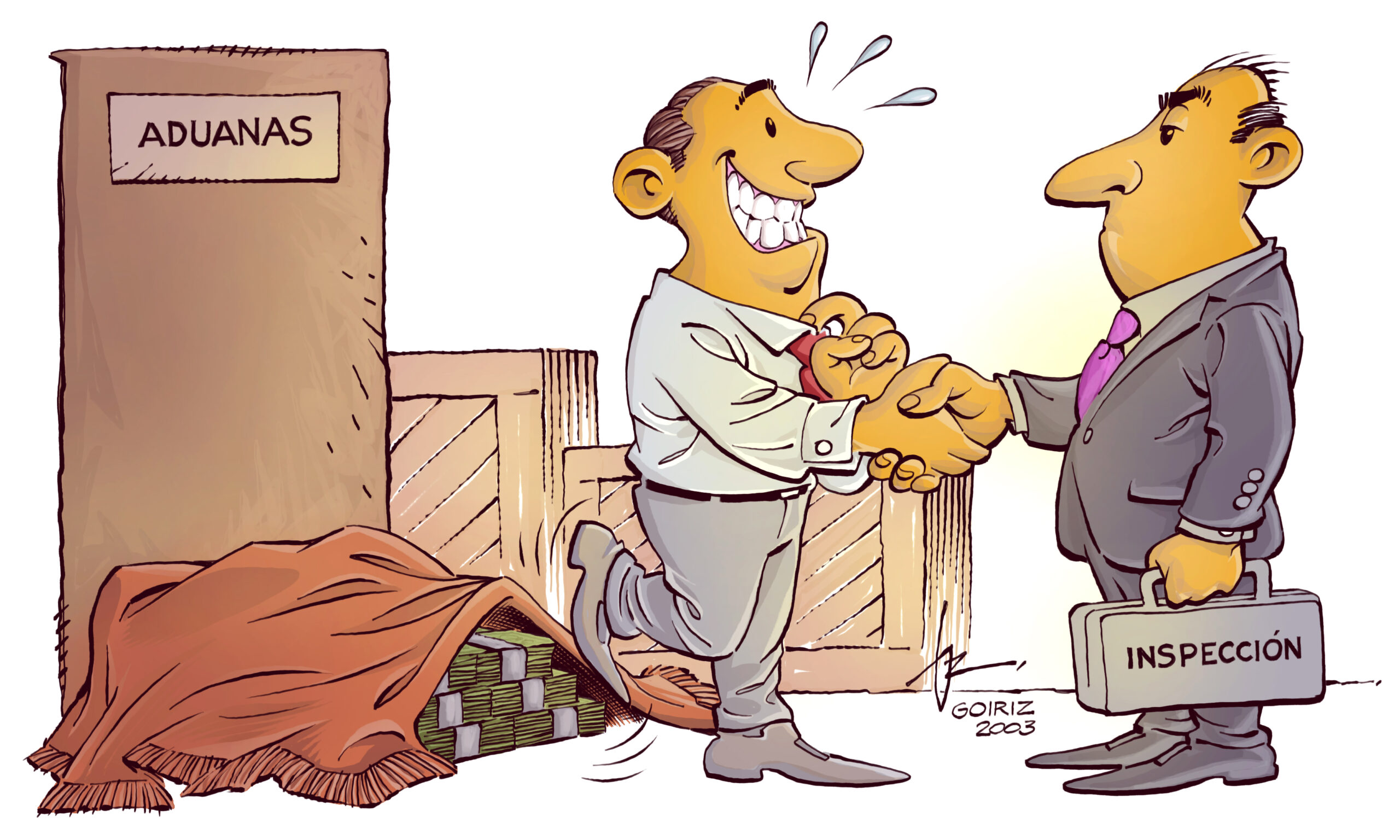

Cover Image: Roberto Goiriz