By Rodrigo Ibarrola

On the afternoon of April 13, after the case of alleged extortion by truck union leaders of the Interior Minister of the government of Mario Abdo Benítez became known, Senator Enrique Riera (ANR-Cartista) announced that he would present a bill to increase the penalties for those who close roads obstructing free transit. His colleague Fernando Silva Facetti (PLRA-llanista) supported the motion, using as justification the supposed effectiveness of the Zavala-Riera Law, which basically led to the crime of trespassing being classified as a crime. Since then, one of the authors of the law, Senator Fidel Zavala (PPQ), constantly pontificates that the law, approved on September 29, 2021, succeeded in bringing invasions down to zero.

However, data from the National Police itself contradicts Zavala. Not only have property invasions not dropped to zero, but the police have reported 56 reports of invasions between October 2021 and March 2022, in the different departments of the country (Figure 1). By far the most affected has been the Central department, one of the most populated in the country and with more infrastructure and police personnel than the other departments.

Figure 1. Reports of encroachment, October 2021 to March 2022

Source: Own elaboration with data from the National Police.

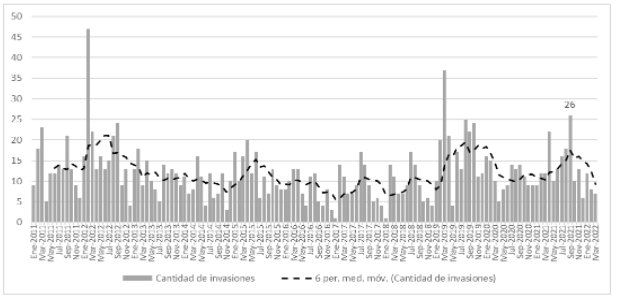

Taking a broader spectrum, say, since 2011 (Figure 2), we see that encroachments show a relatively stable pattern with some punctual peaks. During the period of Horacio Cartes (2013-2018), encroachments remained relatively stable and without sharp peaks, and no law was needed for that. Although never, at least, in the last eleven years, did a single month go by without invasions and it will probably never happen.

Based on evidence, academia has long addressed this issue with the conclusion that increasing penalties as a criminal policy lacks empirical support (see, for example, that marijuana production in the country has done nothing but increase over the years, despite the increased repressive structure in its supposed combat). Even less so if the phenomenon has structural origins, such as poverty, inequality, and the legality of land in the possession of large landowners.

Nor is it true that before the Zavala-Riera Law there was an average of 26 invasions per month, as stated by Senator Silva. That number corresponded to a monthly peak (September 2021), which was skillfully exploited by the promoters of the law. In fact, if we were to find an average, we would see that it remained well below the 26 invasions highlighted by Senator Silva, despite the leap in absolute terms in the month of September. Already at the time, using data from the Public Prosecutor’s Office, Senator Pedro Santa Cruz (PDP) had pointed out that “there is no such wave of invasions”. The National Police data also supports his statement.

Figure 2. Reports of trespassing, by month, 2011-2022

Source: Own, with data from the National Police.

Even if invasions had dropped significantly after the approval of the law, would that mean that the law had the expected effect? No. Phenomena, especially social phenomena, rarely depend on a single factor. To prove it, other factors would have to be included in the equation, either to measure their impact or to rule them out. In addition, the decrease in the number of invasions could be because the police have increased their number or carried out more eviction procedures (or “cease and desist” operations, as they are called when they proceed without a court order) or that the landowners’ capangas have begun to operate in the area. It could also be that the economy that year has improved at certain times (increasing relative well-being) or that the social groups have reached an agreement or truce. None of these factors is contemplated in the mere registry of invasion reports. Therefore, for a correct evaluation, all these factors should be considered and for a longer period of time.

Based on evidence, academia has long addressed this issue with the conclusion that increasing penalties as a criminal policy lacks empirical support (see, for example, that marijuana production in the country has done nothing but increase over the years, despite the increased repressive structure in its supposed combat). Even less so if the phenomenon has structural origins, such as poverty, inequality, and the legality of land in the possession of large landowners. We must emphasize this last point since Paraguay has more square kilometers in land titles than in land area. In fact, a recent article in Clarín recommend potential Argentine investors to “make a title study before buying (land)” in Paraguay. This is one of the main sources of conflict generating forced evictions and human rights violations.

In conclusion, Senators Silva and Zavala’s assertions are false. Neither the average number of invasions was 26 nor did they drop to zero after the Zavala-Riera Law went into effect. Punitive power does not solve social problems; to convert offences that fall disproportionately on the less favored population into crimes is a classist and exclusionary policy. It is essential to note this and, above all, to combat this new repressive and authoritarian move.

Cover image: ABC Color