By Marcos Pérez Talia

There is a certain consensus in the academic world that something is happening to democracies in all latitudes. Different authors, from different areas of the social sciences, have been warning about a crisis of democracy, whether in terms of an eventual democratic regression, or even a process of democratic mutation. An authoritative voice on the subject is the French sociologist Pierre Rosanvallon, who in his book entitled “Democratic Legitimacy” explores the possible causes of the crisis. This article addresses the phenomenon of Paraguay’s (weak) democracy based on Pierre Rosanvallon’s analytical proposal.

In his acute book, Rosanvallon sets out to examine the principles of legitimacy of democratic governments with the aim of interpreting the root causes of their multiple crises. Between the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the author indicates that two major legitimacies developed: one, popular election, and the other, public administration. Regarding the first, the installation of democratic governments between the end of the 20th century and the beginning of the 20th century (especially in the USA and France) was essentially based on the electoral procedure as the only means of access to representative positions and, to a certain extent, as a natural expression of popular sovereignty. The circumstantial majority that elected authorities was even equated with popular sovereignty itself, even though it was only a provisional majority that could eventually be modified in the following elections.

At the beginning of the 20th century, according to Rosanvallon, the first great crisis of democracy appeared with the signs of estrangement between the representatives and the people. Consequently, the second source of legitimacy emerges: public administration. This led to the transformation of the state from a mere guardian of public freedoms and private property to one that offered basic public services such as health, education, housing and higher levels of infrastructure.

Thus, a democratic system of dual legitimacy was established, one of entry or establishment (electoral), and the other of results (public administration). This system of dual legitimacy will sustain a large part of the democracies throughout the 20th century.

Regarding dual legitimacy, in this paper I hypothesize that Paraguayan democracy has severe problems with the legitimacy of results (public administration) and, considering the 2018 general elections, the legitimacy of input (electoral) may also be aggravated. As a matter of space, we will briefly discuss here the tensions of electoral legitimacy, leaving for a second article the legitimacy of results.

Paraguayan history prior to 1989 is not rich in democratic electoral processes. The only relatively free, clean, and competitive election was in 1928, during the government of Eligio Ayala. The striking thing about this case is that we are facing one of the oldest and most persistent two-party systems in Latin America, which, however, did not have the capacity to organize democratic elections within the framework of its inter-party competition.

With the beginning of the transition to democracy in 1989, the electoral dimension became central in the democratizing agenda of the political elite, relegating almost to ostracism any debate regarding the democracy of results. The 1992 Constitution created the Superior Tribunal of Electoral Justice (TSJE) and a few years later, by means of the well-remembered “governability pact”, its authorities were constituted not only with colorado members but also with the parliamentary opposition. In 1996 the second municipal elections of the democratic era were held, with two important novelties: the plural incorporation of the highest electoral authority and the enforcement of a new electoral code (law 834/96). This new policy of shared responsibility and mutual control between parties soon yielded results. Elections became free, clean, and competitive, which, in a way, ensured the consolidation of the political system.

While recognizing the chronic anomalies that affect our electoral processes, such as vote buying, unequal composition of the voting tables and occasional problems with the electoral rolls, in general, the most remarkable aspect of the Paraguayan democratic system was its electoral dimension, which was fully in line with Robert Dahl‘s postulates of procedural (or polyarchic) democracy. In a well-known academic work, published more than two decades ago, it was pointed out that Paraguayan democracy was of very low quality, offering poor results in almost all the dimensions of quality considered in the study, except in one: that of electoral processes, which presented satisfactory results comparable to the rest of the countries in the region.

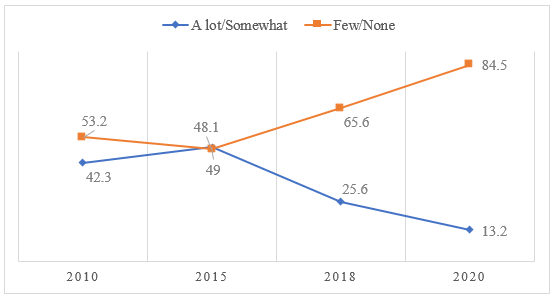

The point is that this minimal or procedural democracy, solved based on free and competitive elections, deteriorated over time. The turning point came in the 2018 general elections, whose results left a blanket of doubts and uncertainties. In fact, the whole electoral process was a strongly flawed product of fraudulent polls that staged a resolute scenario, added to the high electoral official promising to increase votes in exchange for money. This naturally ends up having an impact on the citizen’s own perception and trust towards the highest electoral authority (TSJE), as shown in the following graph.

Graph I. Confidence in Electoral Justice (TSJE)

Source: Own creation, based on Latinobarómetro database.

Latinobarómetro data show that, starting in 2018, the trend towards disapproval of the TSJE was in crescendo. And in 2020 (the last measurement), there was a sharp increase towards little and no confidence, reaching a calamitous percentage of 84.5%.

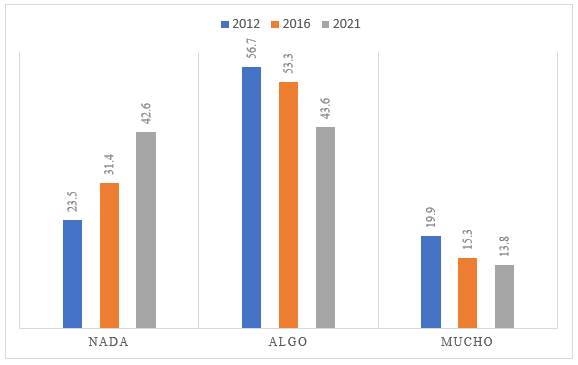

From another angle, LAPOP offers us statistical data on how much confidence Paraguayan citizens have in the elections, the results of which seem to confirm the trend.

Graph II. Confidence in elections

Source: Own elaboration based on LAPOP database.

The erosion of confidence in elections is observed year after year. For example, the “none” response almost doubled from 2012 (23.5%) to 2021 (42.6%). The same decline occurs with the response “a lot”, where in 2012 it was 19.9% and in 2021 only 13.8%.

The point is that this minimal or procedural democracy, solved based on free and competitive elections, deteriorated over time. The turning point came in the 2018 general elections, whose results left a blanket of doubts and uncertainties. In fact, the whole electoral process was a strongly flawed product of fraudulent polls that staged a resolute scenario, added to the high electoral official promising to increase votes in exchange for money. This naturally ends up having an impact on the citizen’s own perception and trust towards the highest electoral authority (TSJE)

This double statistical angle is interesting because, when we observe confidence in the Electoral Justice (graph I), the focus of attention is strictly on the institutional authority. On the other hand, when we calculate confidence in elections (graph II), it goes beyond the strictly institutional (the TSJE) and other actors in the democratic game, such as political parties, candidates, electorate, etc., enter the evaluation. Both data show that our once virtuous procedural (or electoral) democracy is losing ground. It is urgent to regain confidence in the legitimacy of origin as a precondition to then give greater meaning and vigor to the legitimacy of results.

In the following article we will discuss the (bad) results of the legitimacy of the results of Paraguayan democracy.

Cover image: ABC Color