By Rodrigo Ibarrola

It is no secret that former Minister of the Interior and the National Anti-Drug Secretariat (SENAD), Arnaldo Giuzzio, and former President Horacio Cartes are enemies. The first one disclosed the alleged mechanism used for the laundering of money from tobacco companies. Meanwhile, Cartes’ referents responded by exposing the alleged link between Giuzzio and the drug trafficker Marcos Vinicius Espínola Marques de Padua (partner of a Tabacalera del Este shareholder), who helped the former minister by renting him a van during his stay in Brazil on vacation.

Another of the facts attributed to Giuzzio by the Cartismo is that, during his time as SENAD minister, he dismantled the Directorate of Air, River and Land Intelligence (DIAFT), which, according to this sector, was in charge of preventing the passage of drugs through the Paraguay-Parana waterway. As a result, Mario Abdo allowed for a “fast lane” for the passage of shipments and the proof would be the increase in seizures in Europe of cargo from Paraguay.

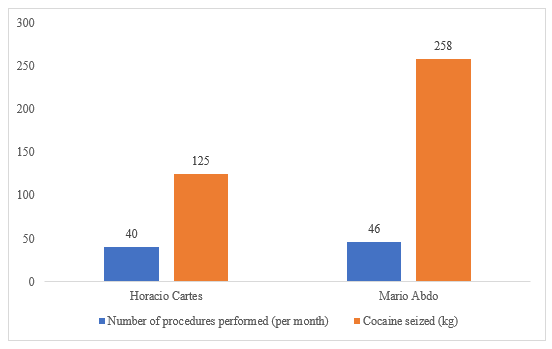

However, a closer look at SENAD’s management reveals that this assertion has little basis in fact. Although it is true that the DIAF has been dismantled, the number of operations has not decreased, but rather increased, as has the volume of cocaine loads seized, as can be seen from the data in Figure 1 regarding the number of operations carried out and the amount of cocaine seized. It should be noted that the number of raids is an international standard for estimating the amount of cocaine circulating in the market.

Figure 1. Monthly average of procedures carried out and cocaine seized

Source: Own, with data provided by SENAD.

Parallel criminal financial networks assist cocaine traffickers not only in money laundering activities, but also in the placement of large amounts of money in source countries and distribution centers to acquire cocaine shipments.

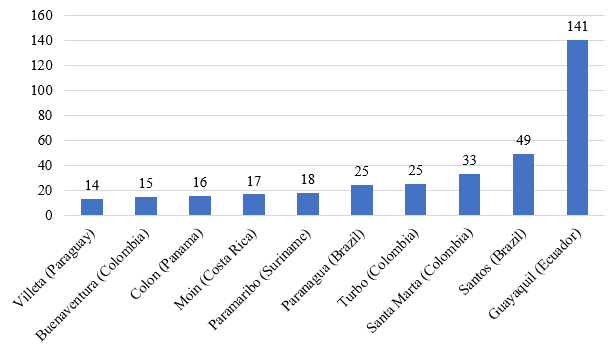

One might think that the phenomenon of seizures of Paraguayan cargo in European ports is a phenomenon caused by actions taken by the government. However, this observation fails to consider a great deal of context. For example, Paraguay was not the only port of origin of the cargo seizures, nor was it the one with the highest volumes. One need only review Europol’s figures on the origin of the mega cargo seizures. Figure 2 shows the main ports of origin of cocaine trafficking to Belgian ports between 2018 and 2021. It shows that Paraguay is number 10 and Guayaquil (Ecuador) is by far the most important port of departure of cocaine to Belgium.

Figure 2. Top 10 ports of origin by quantity of cocaine destined for Belgian ports seized in 2018-2021, in tons

Source: Own, with Europol data.

Figure 3 shows the amount of cocaine seized in other European ports by origin. Here we see that Guayaquil and Santos continue to be the main ports of origin, with Villeta in the next group of ports without much difference between them.

Figure 3. Top 10 source ports by quantity of cocaine destined for other EU ports seized in 2018-2021, in tons

Source: Own, with Europol data.

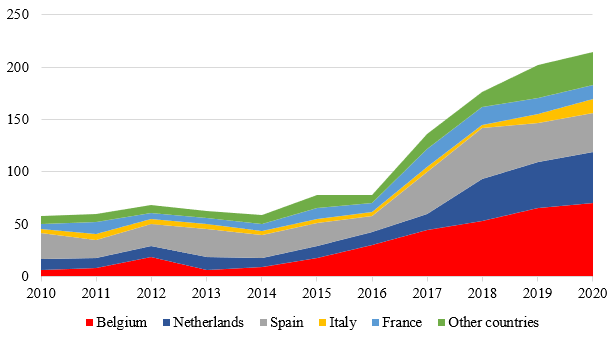

As can be seen, Paraguay is neither the only country of origin nor the largest in volume. In fact, it is a minor player in the region compared to the others. Observing the evolution over time, seizures in Europe had a substantial increase starting in 2017 (Figure 4). That is, coinciding with the end of Cartes’ term in office. Since then, there has been a sustained increase during Mario Abdo’s term. Given this circumstance, it is at the very least imprudent to point to one person as the culprit of this situation. The causes are far from our country and are more complex.

Volume of cocaine seized, in tons

Source: Own, with Europol data.

Since 2017, record amounts of cocaine have been seized in Europe every year, especially in seaports. In 2020, the largest amount ever recorded, 214.6 tons, was intercepted. Preliminary aggregate data shows that the 2021 total was even higher, with seizures of 240 tons having been reported up to the time of the latest published report.

It stands to reason that seizures are an indicator of increasing supply, in turn, driven by demand. Indeed, data from sewage analysis in European cities show an 80% increase in cocaine use since 2016.

Aggregate trends of cocaine residues in 8 EU cities 2011 to 2021, mg/1000 inhabitants/ per day

Source: Monitoring Center for Drugs and Addiction (EMCDDA).

Note: Trends in daily average amounts of benzoylecgonine in milligrams per 1000 inhabitants in Antwerp Zuid (Belgium), Zagreb (Croatia), Paris Seine Centre (France), Milan (Italy), Eindhoven and Utrecht (The Netherlands), Castellón and Santiago (Spain). These 8 cities were selected due to the availability of annual data from 2011 to 2021.

But what has driven this explosion in cocaine use? One of the factors behind this phenomenon is the retail price of the product, which has been becoming more affordable since 2015. The substantial profits associated with cocaine trafficking have attracted numerous European-based criminal networks into the business. Most of the criminal networks have been active for over 10 years, however, new players seeking a larger share of the cocaine market such as Albanian, Belgian, British, Dutch, French, Irish, Moroccan, Serbian, Spanish and Turkish networks have joined in. Figure 6 shows how the average price per gram of cocaine in Europe has fallen. Thus, a gram that costs ₲25,000 in Asunción (marketed in 2-gram bags for ₲50,000), in Europe has an average value of almost ₲1,200,000 at the current exchange rate. The margin is remarkable and, above all, appealing.

Average Affordability, euro/gram

This competition between groups led to an increase in criminal network operations (and thus supply) and a reduction in the cost of cocaine, driving demand. Cocaine continues to be produced mainly by Colombian networks. These, in turn, cooperate with other criminal networks in South America and the European Union, and keep a physical presence in transit countries. For example, Brazilian criminal networks have become partners with Colombian networks and buy cocaine produced in Bolivia and Peru. In addition to their trafficking activities, they are service providers for criminal gangs that operate globally and use the ports to traffic cocaine. The same is done by Mexican cartels with large cocaine shipments through South American ports to Europe.

This complex web of drug trafficking has required the participation of professionals from multiple areas such as lawyers, bank employees, accountants, money launderers, computer scientists, chemists, mechanics, investigators and hit men. Parallel criminal financial networks assist cocaine traffickers not only in money laundering activities, but also in the placement of large amounts of money in source countries and distribution centers to acquire cocaine shipments.

What we conclude from all this is that it is not true that a simple administrative provision has caused the significant increase in cocaine trafficking. The causes are much more complex than they appear. Any moderately rigorous analysis should consider all aspects of what is clearly a global phenomenon.

Cover image: Agencia IP