*Por Jorge Rolón Luna

Throughout the decades that the drug trade has been active in Paraguay, the active involvement of state agents has become evident. We’ve seen them trafficking, facilitating, concealing, financing, associating, and even selling the suspension of law enforcement.

However, in this article, I argue that it remains inaccurate to label Paraguay as a “narco-state.” Other “criteria” should exist to characterize a country as such. For instance, the drug trade should overshadow other economic activities, and there should be vast areas of illegal cultivation within the country.

Various estimates place the hectares dedicated to cannabis cultivation between 6,000 and 7,000, with some suggesting up to 20,000. In contrast, soy cultivation alone occupies 3,300,000 hectares, a comparison that speaks for itself. Determining the total revenue from the drug trade is challenging due to its clandestine nature, but estimates range from $1.5 billion annually for both marijuana and cocaine to nearly $7 billion annually for cocaine alone.

The Paraguayan state, adept at juggling various forms of corruption, condones, abets, and collaborates with private entities in extensive corruption schemes that span a range of illegal activities: theft, smuggling, counterfeiting, public procurement, and tax evasion, among others. Therefore, if Paraguay isn’t labeled a narco-state, it isn’t for a lack of public complicity or involvement in the drug trade.

Several reasons discredit the narco-state label. Firstly, there’s no academic consensus on the level, amount, or percentage of state involvement with drug trafficking required to label a country as a narco-state. Those who advocate for the existence of narco-states don’t clarify the threshold of land cultivation, exports, or GDP percentage that qualifies a country as one.

To better understand the relationship between the state and drug trafficking groups, other conceptual constructs might be more useful. For example, the categories of predatory, parasitic, and symbiotic relationships between criminal groups and the state can provide insights into the Paraguayan situation. In a predatory relationship, criminal gangs exist without threatening the state or security forces. In a parasitic bond, state corruption allows complicity within security forces, the judiciary, and the general bureaucracy. In a symbiotic relationship, there’s a fusion between criminal groups and corrupt state agents, allowing the former to use the state for their benefit.

Another category focuses on networks of macro-criminality, state capture, and co-optation. This model highlights various interactions between de facto powers and the state, characterized by networked structures involving the public sector in a systemic manner, also involving business, criminal, and political structures, which can end up capturing parts of the state.

A recent study from the University of Cambridge, specifically on the Paraguayan case and others like it, analyzes the category of “criminal politics.” This perspective looks at the connections between criminal groups, politicians, and state agents, who jointly pursue their agendas and goals.

Another model to understand the situation in Paraguay is the concept of clandestine order — clusters of order, which analyzes the Argentine case. This model describes a political power that thrives due to a “constant buying and selling of protection that acts as a shield isolating state power, capturing and commercializing it to allow illicit businesses to prosper” (the state’s mafia arm).

A frequently used concept is criminal governance, a criminal power that emerges in the state’s shadow, not to challenge it but to generate interaction between criminal groups, society, and public power.

Lastly, the concept of “crimilegality” is of interest. This approach refers to the blurred line separating legal from illegal businesses and emphasizes that organized crime has shifted from operating on the fringes of political order to becoming an integral part of it.

All these perspectives share commonalities: one is the active role of the state and its agents, which challenges the views of a “weak” or “absent” state and questions the separation between the state and criminal groups. Another commonality is the need to stop considering criminal groups as an entity operating for profit maximization and being essentially external to the political order. This naive view believes in the “war on drugs” and calls for larger budgets to “fight drug trafficking.”

The reasons to discredit the narco-state label are many. Firstly, there’s no academic precision regarding the level, amount, or percentage of state involvement with drug trafficking required to label a country as a narco-state. Those who advocate for the existence of narco-states don’t clarify the threshold of land cultivation, exports, or GDP percentage that qualifies a country as one.

Furthermore, the narco-state concept is vague; it’s more political than technical. The intense activity or presence of criminal groups in certain territories or the undeniable involvement of politicians, security forces, or fractions of bureaucracy can be misleading. They don’t signify the state’s defeat against an enemy but other phenomena that need analysis and explanation.

Therefore, from a broad perspective, it’s possible to assert that, firstly, the narco-state concept poses serious problems and, secondly, for multiple reasons, it’s not suitable to characterize the Paraguayan reality. Other theoretical models can do so more accurately.

*Researcher. Former director of the Observatory of Coexistence and Citizen Security of the Ministry of the Interior.

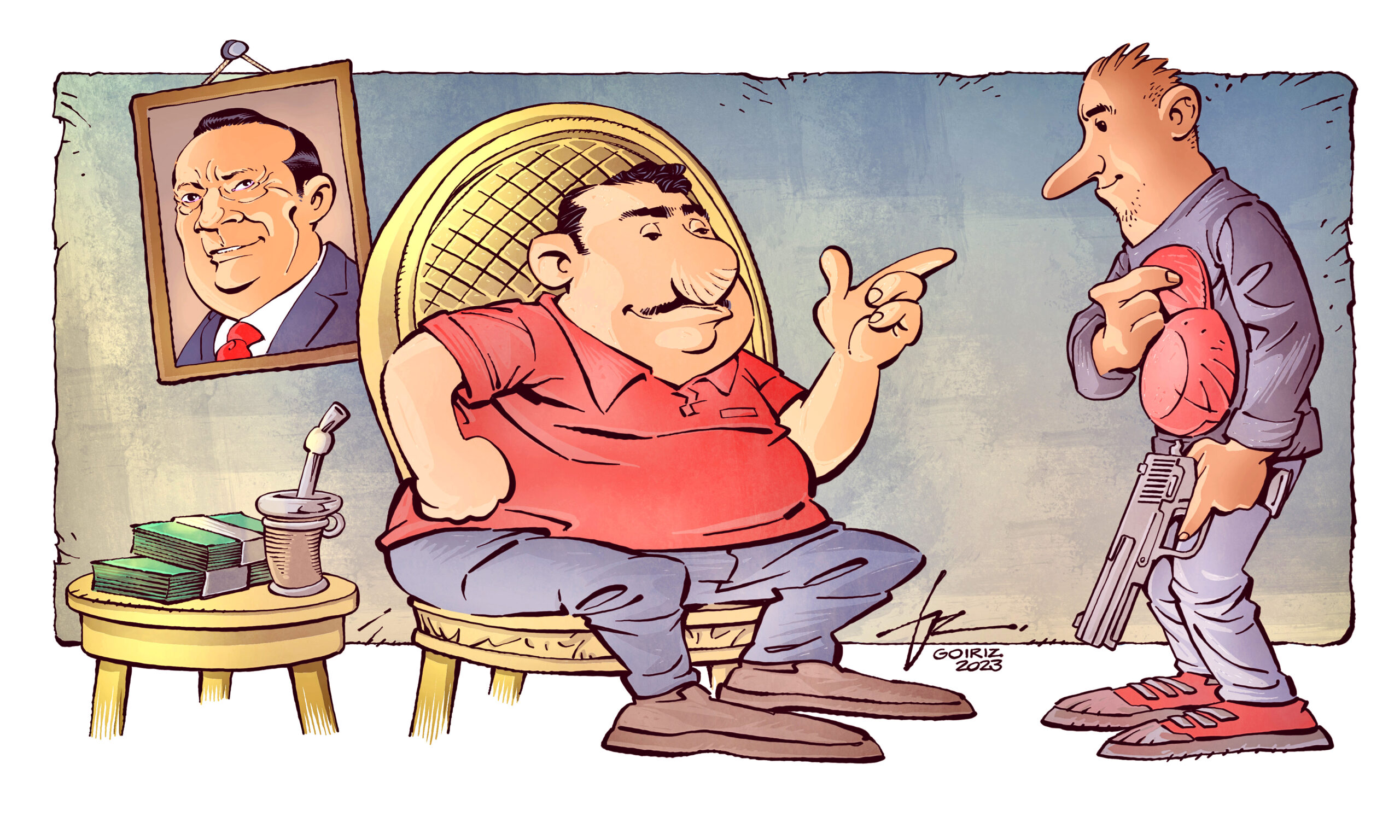

Cover image: Roberto Goiriz.