By Jorge Rolón Luna*

In a previous article it was stated that homicide is the worst and most extreme form of censorship. It represents the clash between the most radical censorship and the right to information, the exercise of which is the precondition for democracy and the rule of law. From another perspective, the murder of journalists shows how hostage to criminal networks a society can be.

When Santiago Leguizamón was murdered in 1991 in the city of Pedro Juan Caballero, it was not only the “inauguration” of the assassination linked to the actions of criminal groups in Paraguay, but also the ultra-violent silencing of journalists through this sinister tool. From that moment until today, almost twenty journalists have been murdered. The country even received international condemnation for its negligence and criminal negligence in the investigation of the case. A balance of these events, where most of the episodes have had a clearly mafia-like stamp, reveals some patterns that should be taken note of.

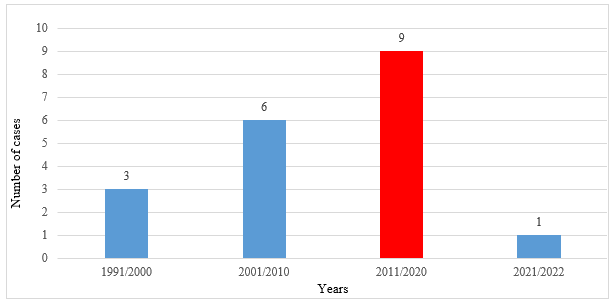

A retrospective analysis shows that since the new century the murders of journalists have been repeated almost year after year, practically without a pause (see graph 1). While in the 90s of the last century there were only 3 cases, between 2001 and 2010 there were 6, and between 2011 and 2020 we already had 9 cases (almost one case per year in that decade). The recent murder of Humberto Coronel opens the present decade.

Murder of journalists per decade – 1991-2022

Source: Own with data from journalistic sources

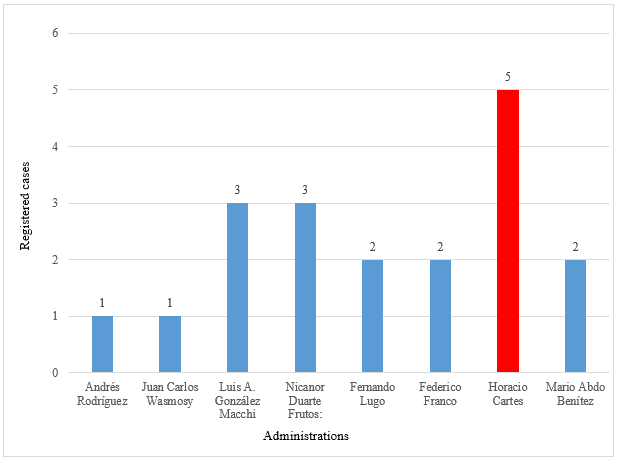

As can be seen in Graph 2, the murders of journalists began under the government of General Andrés Rodríguez, who was one of the precursors of the drug trafficking business during the dictatorship of Alfredo Stroessner (1954-1989). It may be equally fortuitous, but it is striking that the highest number of murders of journalists the record, occurred during the government of Horacio Cartes. The business relationship of the former president with known and suspected drug traffickers, in addition to episodes of finding drug planes in his properties, always generated suspicions. During his government 5 journalists were murdered, compared to 3 cases during the governments of Nicanor Duarte Frutos and Luis A. González Macchi, 2 cases during the governments of Fernando Lugo (who governed for 4 years) and Federico Franco (who only governed for one year). In the governments of Mario Abdo Benítez (who has not yet completed his presidential term) and of Andrés Rodríguez and Juan Carlos Wasmosy, there was 1 case in each period.

Murders of journalists by presidential administration/period 1991-2022

Source: Own with data from publications

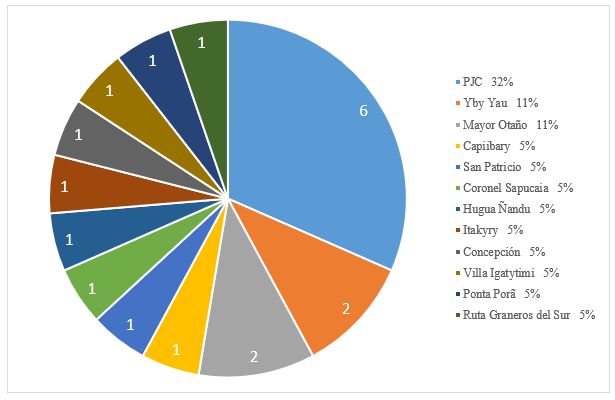

Graph 3 illustrates the geolocation of the murders of journalists and it can be seen that Pedro Juan Caballero is the city where more journalists have been murdered (6 cases). In this city also a radio station had its antenna knocked down in 2015 and suffered an attack with grenades – yes, grenades – in 2016, not to mention that one of its journalists had been murdered in 2014. It is followed by Concepción, with 4 cases (21%) and is another “narco” border place, also risky for journalism.

Graph 3. Journalists murdered by town 1991-2022. In percentages

Source: Own with data from journalistic sources

The departmental geolocation shown in Graph 4 makes it possible to clearly see the relationship between the murder of journalists and the illegal drug trafficking business. Although some cases in these years could be related to other causes, all the murders of journalists since the beginning of the phenomenon occurred, except for one, in border departments. The murders occurred in Amambay, Concepción, Itapúa, Canindeyú, Misiones, Alto Paraná, places that were already pointed out by the IACHR as “silenced zones”, places “extremely dangerous” for journalists. places “extremely dangerous” for the exercise of informative work. Regarding the only case that did not happen in a border department, the exception is not such, since it happened in the department of San Pedro, adjacent, in turn, to the departments with the highest drug trafficking activity in the country, such as Amambay, Concepción and Canindeyú, all bordering Brazil.

Murder of journalists by department 1991-2022. In percentages

Source: Own with data from publications

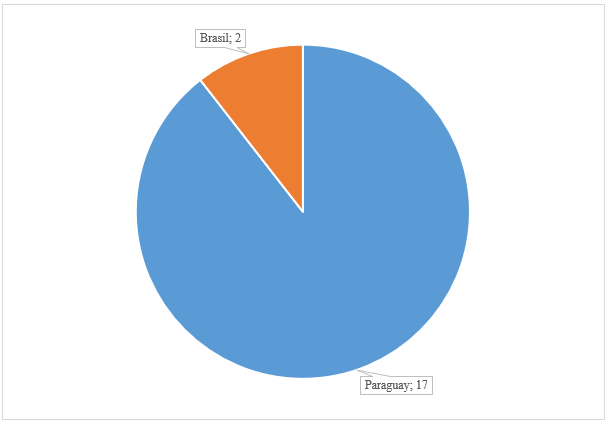

Graph 5 shows the following curiosity. Two of the murders of Paraguayan journalists or of journalists working in Paraguayan media (this is what is usually taken as a parameter to quantify the phenomenon) occurred in Brazilian territory. These cities are Ponta Porã and Coronel Sapucaia, border cities located in the state of Mato Grosso do Sul.

Murder of journalists according to country of occurrence 1991-2022

Source: Own elaboration with data from journalistic sources

On the other hand, Graph 6 shows that, of the 19 victims, 16 are Paraguayan nationals and 2 are Brazilian (although both have Paraguayan ancestors). These are the journalist Leo Veras, who had a Paraguayan mother, and the communicator Samuel Román, of Paraguayan parents. There was also a victim of Chilean nationality, Alberto Tito Palma.

Figure 6. Journalists killed by nationality 1991-2022

Source: Own with data from publications

In Paraguay, the patterns of murders of journalists in Latin America are repeated, with victims who do not come from large urban centers, work for several small, local or community media, and in precarious employment situations. Nor is there a single case of a single communicator who has been a victim while covering risky assignments. All of them were deliberate murders, where they were the target of their victimizers.

When Santiago Leguizamón was murdered in 1991 in the city of Pedro Juan Caballero, it was not only the “inauguration” of the assassination linked to the actions of criminal groups in Paraguay, but also the ultra-violent silencing of journalists through this sinister tool. From that moment until today, almost twenty journalists have been murdered.

A disturbing and shocking fact is also that, in the cases of the murdered communicators Yamila Cantero and Ángela Acosta, they were attacked by police officers. These events were never clarified and the official version labeled them “crimes of passion”. In the first case, the murder would have taken place in a police station and then the perpetrator would have committed suicide, although no other policeman present in the police station on that occasion heard any gunshots. In the second case, suspicions were directed towards a uniformed officer, Agustín Alfonso Verón, her alleged boyfriend, who had been seen with her before she was found shot on a country road 180 km from Encarnación. Even more disturbing is that the policeman Verón was later linked to the murder of another journalist, Alberto Tito Palma, also in Mayor Otaño, Itapúa. In other words, in a very short period two journalists were murdered in the same area (where homicides rarely occur) and the main suspect was the same police officer. Thus, the hypothesis of an alleged “crime of passion” only seemed to be a smokescreen for an event that seriously compromised the Paraguayan State.

Without exhausting this essentially quantitative analysis, most of these cases have remained so far with varying degrees of impunity. Some were never cleared up, others were cleared up but not punished, others were partially punished (the material perpetrators were convicted, but not the masterminds) and none had a conclusive investigation to punish the material and intellectual authors. One last issue is coincidentally linked to the issue of punishment for these crimes.

During this time, two journalist brothers were murdered (Salvador and Pablo Medina), being the only cases solved in a more or less satisfactory way: 2 out of 19, 10.5% of the total, below the world average of cases of journalists’ murders solved, which in 2020 was 13% according to the United Nations. In short, Paraguay neither protects journalists nor punishes their executioners.

*Lawyer, teacher, and independent researcher. Former Director of the Observatory of Security and Citizen Coexistence of the Ministry of the Interior.

Cover image: NEA HOY